Soviet Paradise

Home Page / About Us / Anna Family / About the 'Sybiraki'

My Journey from Poland to England via "the Soviet Paradise"

Left hand side poem entitled 'Memories of an Exile - 13.04.1940' by M. Sieniawska (to be translated)

Krystyna J Wariwoda (née Hajos)

A History of my journey from Poland to England via the "Soviet Paradise"

The Last days of Freedom

My fathers' foresters lodge stood in a wooded clearing close to the settlement of Cimliwo. Father was employed by the Forestry Commission in the primeval forest of Białowieża as a forester. The lodge was built of wood and stood back a few metres from the forest road. The outbuildings lay at the edge of the forest. The property was quite sizeable.

At night, the greatest enemy of the hen house was the fox. During the day it was the goshawk.

When I lived in the lodge I used to see how the geese and the turkey-hens defended their chicks. When the enemy (goshawk) appeared the turkey-hens let out an almighty shriek, alerting their chicks to the danger. Immediately the chicks would hide under the closest leaves or melted into the grassy meadows so that they could not be seen, the mother hen then circled around constantly and kept watch. After a very long while her agitation abated and she called out a less harsh warning that they should still stay hidden.

Guinea fowl chicks, with their distinctive pink feet, disappeared with lightning speed off the face of the earth. Hen chicks, though, were the least resourceful with the result that many of them perished. The ganders on the other hand went into battle. The goslings bunched together and hid beneath their mothers' outstretched wings. They then stretched their necks and heads skywards. The ganders would jump up to fight off the attacking goshawk.

The last time I was witness to this drama the raid was unsuccessful, he flew off empty handed. But the yard remained deserted for a very long time. The mothers kept up their warning calls - those of the turkey-hens seemed endless. A complete silence descended and only then did she call out her young which started emerging from under the leaves and out of the nooks and crannies in the garden to which they had fled. The chicks then ran around in their usual carefree manner.

This, then, was the setting for my last few months of freedom - carefree and in Mother Natures' womb.

September 1939 brought us the terrible news - war!

Shattered remnants of army units passed along the silent forest trails. These were quickly followed by private carriages and wagons belonging to people fleeing from the front line. Occasionally we would hear the drone of an aeroplane flying above the forest. The silent forest became a witness to human tragedy. The people passing through left us their hunting guns and we hid them in our lodge.

Autumn 1939

But it wasn't just the people who suffered - a tragedy also played out in the forest and became a place of suffering. This autumn was stormy and a state of near anarchy reigned. Local farmers cut down the most noble trees for their own use. Poachers hunted animals openly without fear of retribution. The new local town authorities arrested father and all the foresters in the Forest Inspectorate in order to interrogate them. This lasted several days and they finally returned home at the beginning of December.

In this atmosphere we approached our first sad Christmas holiday. There were four of us at home. Father, Mother, me and my younger brother who was still at grammar school. Then my brother was informed that he was to be interrogated to reveal where we had hidden the guns - he was given a deadline of the New Year to speak out. Naturally my brother had no intention of doing anything of the sort, so in order to avoid being arrested he had to flee before the New Year.

The winter of 1940 was very harsh. The world was blanketed in snow and covered with sparkling ice crystals, as if to say "look at me, look at how beautiful I am" and it was beautiful. On such a moonlit night, there was nothing more wonderful than to harness a black horse to a sleigh, snuggle down in a warm sheepskin coat and speed along a crunchy snowy landscape, passing trees groaning under the weight of the snow; but these are just long lost memories now.

On a freezing, starry night I drove my brother to Białowieża. All he had with him was a small bundle containing a change of linen, a small sum of money and a small revolver in his pocket. He was going to our family in Kraków.

As I mentioned before that winter in 1940 was very severe. The border crossing was dangerous. He got frostbite when he fell asleep under a dripping gutter in the freezing rain. He only just managed to get to the family alive. Then, under the German occupation he was forced to become a slave labourer building roads.

Neither he nor I had any idea of what fate had in store for us - we were parted for many, many years!

We only had 40 days left in Poland (but of course none of us knew that at the time). And, although the winter was very severe, it was warm and cosy at home because we never lacked for firewood, however the same was not true of food. Sometimes local farmers brought us a loaf of dark, peasant bread. This was their way of showing gratitude to their forester.

That winter was different, the frost deepened, food became scarce, the days became monotonous. Then came the 10th February 1940, probably the coldest day of the year. At 4.00 o'clock in the morning, when the frost is at its deepest, a sleigh with janissaries (small bells attached to the horses' collars) drew up outside our lodge.

We heard loud knocking from rifle butts banging on the door and shouts (in Russian of course) of "Open up!" We leapt out of our beds - father, mother and I. We dragged on what clothing we had to hand - and father opened the door. Russian soldiers with rifles in their hands looked like wild animals. They stood us up against a wall - search!

We stood there in our nightclothes, against the wall, a Russian soldier with a rifle in his hands guarded these unarmed "criminals".

"They'll never find them" flashed through my mind like a bolt of lightning. The guns left behind by those people fleeing from the front and fathers' own hunting weapons were safely buried and bricked over in our newly built cellar.

We were not allowed to speak to each other as we stood against the wall. The search began. Books were thrown from their shelves, kicked and trampled on by Soviet boots. They overturned the furniture and since they could not find any weapons, which is what they were searching for, they ordered us to get dressed. They demolished our home before the search ended. But, luck was with us and they did not find the weapons. They told us to pack some clothing, pots and pans, food and bedding - just a few items - they said "You won't need to take much, you'll get everything you need when you get there." So we left with our bundles, all our goods and chattels, pushed out and prodded with their rifles.

We were told to get into a large peasant sleigh strewn with hay. We bade farewell to our forest lodge in Cimliwo that morning, forever.

So that is how our journey into the unknown began in the early morning of the 10th of February 1940.

That day, the 10th of February 1940 my parents lost everything they had ever possessed.

Even after all these years I can still vividly recall one unforgettable memory.

Our beautiful half Arabian black horse was harnessed to a light sleigh in which sat the NKVD* agents who had arrested us. He followed our sleigh as if he knew that it was his masters' last journey. He snorted and ran as closely as he could to our sleigh - he was saying goodbye in his own way.

We were taken under escort to the station at Świsłocz.

First we were taken to the nearest village and kept under guard in one of the houses until the evening.

The NKVD commandeered our sleigh and beautiful horse, a half Arabian called "Żuk" (Beetle) on account of his coat which gleamed in the sunlight mimicking the shell of a black beetle.

Once again we were loaded into the sleigh - we recognised the road as the one leading to the train station in Świsłocz.

A very long goods train with cattle trucks awaited us at the station. On the train father recognised his friends from the Oszczep forest inspectorate and many others. Employees of the Świsłocz primeval forest were also here, - this was the private property belonging to the Tyszkiewicz heirs.

The rest of the train was filled with settlers who had been given land grants in the east after the first world war.

We knew we had lost our properties and freedom. On that day began the life of a person who had had their liberty taken away from them.

We were loaded into the cattle trucks which had been modified. Wooden pallets had been strewn with hay - these were our beds on which we lay or crouched all through the seemingly endless two week journey. There were no windows so it was totally dark and only the feeble light from an oil lamp helped us to move around.

We scrambled up into our allotted shelf. We were beyond all thought, turned to stone by the experiences of that day. Suddenly I heard a soft childish voice say "Auntie" and a pair of soft warm arms wrapped themselves around my neck. It was the tiny three year old daughter of one of our foresters. Her mother, who was expecting her second child, was completely broken by the days' events. So, I adopted the little girl (Poor child, two years later both she and her tiny sister died of dysentery in Kazakstan).

There was a round iron stove mounted in the centre of the wagon, this served as a heater and oven, next to it was a covered container which served as our toilet. The stench in the wagon was indescribable. Chinks in the walls of the wagon let in some precious clean air and also served as our "window on the world." At least we could see something. We read the names of the Stations at Baranowicze, Smoleńsk, Ufa. We were under no illusion that we were heading for Siberia. This was our "first class, luxurious" journey to the Soviet "Eden".

Close to Czelabińsk are copper ore mines. We had been sent there. We were unloaded at Karabasz and settled in a school in what looked like the gym. Each family had a space allocated to them, right next to each other. There was only enough room to lay down prone on the floor. Living and sanitary conditions in that hall were worse than those for cattle. The snow brought in on our boots melted and so the area around the door was constantly soaked, as were the narrow passages between each family's space resulting in damp bedding that never had the opportunity to dry out.

Karabasz is in the Urals on the Asiatic side. The Urals in winter are spectacularly beautiful. Winter lasts for seven moths of the year from October to May. Spring on the other had comes very quickly - one day the world was white, the next all the snow had melted in an instant and immediately everything became green.

And so the NKVD issued their first directive: "When the snows melt you will build huts for yourselves."

May 1940 - June 1941

When the snow melted in May we began to build our huts. They brought us the building materials and and we built our own Polish settlement. There was no choosing which jobs we could do.

A group of women, to which I belonged, dug out the pits for the foundations of the huts. We carried rocks, mixed the mortar and took it to the bricklayers (the huts themselves were made of wood). Lastly we carried the bricks for the chimneys.

Autumn 1941

Our wages were negligible. Father worked as a stoker in one of the factories. He had to ensure that the temperature did not drop below a certain level. He worked every shift but despite that the pay was inadequate. We did not have enough to subsist.

We were forced to sell anything we could. One market day in the town, I went to sell a ladies wristwatch. It was gilt and the worse for wear. It's timekeeping was erratic but once it was wound up it kept good time for about an hour. I knew that wristwatches were sought after and was prepared for any eventuality. I polished it up until it gleamed and went off to sell it. Just before I got to the market I wound it up. The watch looked nice and ticked reassuringly. Just what I needed. I found a buyer very quickly, got a very good price for it and fled as fast as I could leaving the market behind me. I was terrified all the way to the settlement. I did have a few regrets and felt a small qualm about my buyer, but what could I have done? - I struck a great bargain!

Once the settlement had been built we were allocated a room for the three of us. It didn't take long for the hut to become infested with bed bugs and cockroaches. They were our constant companions until we left.

When the huts had been completed our group was sent to help with the building of a factory. We carried mortar and filled in the spaces between the bricks.

Now I should like to tell you why my parents and I were moved to another settlement and placed in a room whose window faced on to the NKVD building.

Two Polish settlements were built in Karabasz in the Urals, one at either end of the town. They were populated with people who had been deported from Poland on the 10th of February 1940. They were mostly forestry workers and re-settled members of Polish Legions. The same fate awaited us all - forced labour deep in Russia - however, the NKVD picked out a group of people who spied for them and informed them of what we said and thought.

When we found ourselves in the situation we were in, we never imagined that there could be informants amongst us, this was extremely naive of us as we had trusted everyone.

Any news that came from Poland circulated around the settlement in a heartbeat. As a result of which our "Soviet Guardian Angels" had no trouble at all in informing the NKVD.

One day I had a letter from Poland and in between the lies the following request was written in invisible ink "We need arms, we know you have a cache in your lodge - tell us where? Stefan"

I replied in the same way using invisible ink to reveal the location. A short while later I got another letter asking why I was delaying the reply. Without hesitating I sent off a second letter.

The approaching winter was very severe, typical of winters in the Urals. Weeks and months went by and then our family was taken to the second settlement under the watchful eye of the NKVD.

I was employed with other women in the copper ore mine, We stood by a belt carrying the ore and had to pinch out any rocks. We did have a roof over our heads but still it was very cold, although we were sheltered from the freezing wind by the walls. We had to go out in shifts to dig the rail tracks which were constantly covered in snow drifts. The icy wind penetrated out clothing and we were chilled to the bone. My clothes were not adapted to these conditions. My legs suffered the most, after every such shift outside, they were stiff and numb like logs of wood.

It was no surprise when I was so ill one day that I did not go to work. I had no idea that I needed a doctor's note. For being absent from work I was tried and sentenced to a fine. For three months I had 30% of my pay forfeited.

During this time I worked the night shift. Every evening the shift workers going to the mine collected each other on the way as it was less intimidating than walking out alone into the black night. One evening, once again I was running a high fever and I had no strength left to get up and go to work. I was thinking of not going, I could hear the voices of our shift coming closer. Suddenly I decided I must get up. Some inner voice ordered me to get up and go. I got dressed at lightning speed and went out to meet the others.

That night seemed endless, the snow fell mercilessly and no efforts seemed to shift it. Next day my fever had heightened but this time I did have a doctor's note. As this was still during my first term of punishment, had I not had a note I would have been given a prison sentence as a criminal against the Soviet Union.

I finished paying my fine in May, but I was not destined to receive full pay for very long.

Winter 1940 - 41

The frost became more severe with each passing day. My father was an excellent walker. As a forester he spent all his days walking through his inspectorate. It was a foresters duty, especially in winter, to oversee the clearances i.e. cutting down trees, treating and cultivating them, fulfilling orders and sending the wood to the railway station.

Winter was in full swing in the Urals. We had to get firewood and this is how we got it.

Father discovered that there was a forest about 10km from our settlement. He went about investigating and researching in total secrecy. As he left the hut he noted the time. When he got to the forest he made a note of the time again. He found some dry wood at the edge of the forest and judged it to be good. It was big and sturdy. He managed to "acquire" an axe, a saw and some strong rope. When he had completed all this he told me we would go to the forest and get firewood.

He had organised and calculated everything. We went out with plenty of time to spare. We had to get to the forest in daylight, cut down the trees and saw them into lengths which would fit onto a sled.

Sawing the wood took a long time but finally the sled was full and we were ready to set off. The day was ending and dusk was approaching. We still had a long way to go before we could rest.

Father harnessed himself to the sled like a horse and I pushed from behind. Night fell very quickly and a starry silvery moonlit sky accompanied us on the way back. Our way was well lit and we went back along our own tracks. The frost crunched underfoot and pinched our faces. It was bitterly cold but we did not feel it.

We got home after midnight but our work was not yet done, we still had to unload and hide our spoils. Only then could we lay down and rest. Morning was not long in coming but we did have firewood for some time to come.

I was still working in the same place. One of the most physically difficult jobs was unloading the slag from the wagons.

The slag was sent back to the mine after the ore had been extracted, in order to fill in the tunnels. Normally the wagons which brought the slag back had a wooden cone in the middle. We would scramble into the wagons with our spades and climb onto the top of the cone. When the side flaps opened we would push the slag out.

One time different wagons with metal cones arrived but we were unaware of this. When the flaps opened we fell out of the wagons along with the slag. Luckily we were only badly bruised. I was given a few days off and they asked me if I could sew. I said of course I could sew. The Russians needed padded jackets for the army, so I was sent to the sewing workshop.

Another time, when we had completely run out of all the basic foodstuffs and the hunger pangs were excruciating, my parents decided to sell their wedding rings and I decided to sell my earrings. There was a government shop, where you could sell gold, in which they said you could buy "anything you needed 'for gold'" - at least that is what they advertised. My parents wedding bands were very wide and made of 18 carat gold. We had hoped to be able to buy essential basic provisions such as fat, a little meat and warm boots.

I arrived at the shop to find it was completely empty! All they had was sweets for sale. The shopkeeper told me to buy the sweets as they were not expecting to get any more. He gave me quite a big bag of sweets for all that gold - that had to be the worst trade I ever made!

We had to increase our output by quite a bit until May so all our shifts were extended by two hours. So, when I was on the late shift I did not get home until 2am.

Our settlement was not too far away from the town. It was now towards the end of February or the beginning of March, when winter in the Urals is at its harshest. One night, after finishing work we went out of the workshop and could not see anything - a blizzard was blowing.

The Russian women dispersed in the town, it was easier for them to get home. I felt quite brave walking though the town and on the edge of it, all I had to do was walk straight ahead. I could not see any sign of the road all I could see was the snowdrifts. I walked on praying as I went. I cannot describe how happy I was to see the first huts and that I had not lost my way.

I was earning reasonably good money at this time due to the extra hours, however I was still paying off my 30% fine.

In June I was arrested and it was all due to a young man who had been deported just like us but who had become an agent for the NKVD.

USSR - The Urals - from Karabasz to prison in Czelabińsk

22 June 1941

One evening there was some strange activity going on outside the NKVD building - cars full of NKVD agents kept arriving and they all dispersed into the whole settlement - no good could come of it all.

We could see everything that was going on from the window of our room. Those who were arrested were taken away in prison vans. We waited anxiously - who would be next? Suddenly we heard heavy boots approaching and a knock on the door - search! "Do not move!"

During the search they found a bundle of letters, silver Polish coins and a camera all of which they confiscated. When they had finished their search they arrested father, told him to get dressed and took him away. They left my mother and me in peace for the time being.

When father had been taken away to an unknown destination in a prison van, the agent who had stayed behind in our room, arrested me. My ailing mother could not believe what was happening but soviet justice has no mercy. Father had said goodbye to us with a look and must have been convinced that we would somehow be able to look after each other, whereas when I was taken away I knew mother would be left alone and would find it difficult to cope.

The prison vans took us to the train and we were taken into solitary cells to Czelabińsk (Chelyabinsk), to the interrogation centre.

I have no idea at all where I spent that first night. I woke up in the morning in some sort of a storeroom, whose windows were barricaded with wooden boards.

I had spent the night on a wooden pallet which served as a bed. My companions were rats which ran around not only the floor but also on me and I nearly died of fright. The night had not in fact been very long but the indescribable nightmare had seemed endless!

Somehow dawn came and through gaps in the boards I could see the prison guards taking prisoners from our settlement. I recognised father among them. After a while they came for me.

The interrogation building was huge, several storeys high and shaped in a horseshoe**.

I was taken to the basement and left in a solitary waiting cell, which was in total darkness. I was left there until the evening. Then I was taken to a cell. It was large and stuffy. There were 11 women prisoners there already, I was the 12th.

They surrounded me eager for news. They had no idea what was going on in the world.

When I started to tell them that the Germans had declared war on the Soviets, one of them kicked my ankle and put a finger up to her lips. They told me later that there was an NKVD spy among them who reported everything that was said. That warning served me well in the future.

After a few days the doors to the cell were opened and a voice shouted "Surname H, pack up your things and follow me!" My immediate thought was - what's going to happen now?

I was taken to the other end of the corridor, to another smaller cell for three prisoners. This was to be home for quite some considerable time. The cell was oblong, it was as long as two lengths of bed boards and as wide as two with a narrow gangway between them. It contained three pallets strewn with straw, Facing the door was a window through which you could glimpse a sliver of sky from the upper half. The rest of the cell was made up of brick walls. That tiny chink was our only light source. The cell was damp and permanently murky.

The two pallets by the window were already taken. The third one by the door on the right was unoccupied, obviously meant for me. Opposite was a container which was our toilet. We used it frequently and the stench rising from it made life truly unbearable. Each morning we were taken to the washroom to attend to our basic needs.

It must have been August. My co-prisoners were teaching me to speak Russian. They told me about themselves and that is how we passed our days. Our food consisted of a slice of dark bread, a bowl of millet porridge and a hot drink. This was our daily ration, it didn't last long. Our rations deteriorated. The slice of bread was smaller, instead of porridge we were given soup, or rather a bowl of hot water in which they had boiled some very small fish, these were cooked whole without removing the scales or heads or guts.

One of my companions had already been there for over a year, she had been imprisoned for her brothers' crime. No-one had bothered about her for a long time. She was not interrogated and no sentence had been passed. While I was there she had a package from home containing a bunch of onions with their green tops still intact. She shared the onions with us. At first I declined her gift as I did not like onions, but she made me eat them. After eating my share I felt full for three days. This is no joke, it really is true.

The second of my companions was a handsome looking factory manager. Her crime was not fulfilling their quotas. She was interrogated from time to time, which always took place at night. Once she was punished for insolence and spent a whole week in solitary on a diet of one slice of bread and a cup of water. Even though we were not allowed any possessions she managed to make some playing cards out of scraps of paper and amused herself by telling our fortunes.

Then my turn came. It was already past midnight, maybe around 2am when the guard came and called out "surname H." He told me to get dressed and come. My first time along the corridors and up the stairs had a devastating effect on me. He took me up two flights of stairs and then to a room where an NKVD agent was waiting. The room was large, clean and well lit. A huge map of the world hung on one wall. The agent sat high above me on a chair, not by the table. The chair was a sort of professional high chair or pulpit. He was screened off. He could look down on me from above but I had to look up to answer him.

After checking my personal; details he informed me that I was accused of collaboration with the Polish underground movement, to the detriment of the USSR and that they wanted to find out about this from me. I was surprised by his questions and asked him how he imagined I could have collaborated from such a great distance.

So the interrogations began. Each night at the same time between 2am and 4am I was taken there for questioning. I gave nothing away during these sessions which angered them. When I got back from the interrogations I was always very agitated and could not sleep. I had to get up at reveille and we were not allowed to lie down during the day. I slept for 4 hours out of 24 which was debilitating in the extreme.

The map in the interrogation room was a life saver. I could see the Vistula river and Warsaw marked on it and something else. Red arrows appeared on the map, one pointing north-east towards - Białystok - Minsk - Moscow and a second pointing south-east towards Lvov - Kiev. Each night they seemed to come to life moving deeper into Russia. After a few days I was almost certain they indicated the front line and that Russia was about to fall. I began to hope that we would be freed.

After a few days when I came into the room I found a woman interrogator was to be in charge of me. She was well dressed and had a good complexion, she sipped tea and on a small plate beside her was a ham roll, which she never touched throughout the interrogation session.

She told me that they had had problems with communicating with me so they asked for a translator. I was to be interrogated through an interpreter. I did not speak much Russian but nevertheless managed to get by.

Within a short time I realised that the interpreter's version of my answers conformed what the interrogator wanted to know. I stopped talking and declared that I would not speak through the interpreter any longer, and fell silent.

The next night the interpreter was not present. We managed without him.

It was the beginning of September, I had been interrogated every night for a month. This particular night the agent was not in a good mood and positively bad tempered. In a raised voice she told me to admit to everything. She screamed at me "We know everything about you!" She took a letter our of her briefcase, it was the one I had written to Poland "this is the letter you sent to the underground, telling them exactly where you had hidden the arms!"

I fell silent - there was nothing more to be said.

The arrows on the map were very encouraging. They continued to move forward! We heard the testing of the alarms in the town. The wailing of the sirens seemed to me like a clarion call to freedom. The all clear was sounded Silence fell all around. But hope had sprung in my heart.

My interrogations were halted for a while. I thought they were preparing for a final trial. A few days later they came for me again at night. But this time they led me in a different direction in the interrogation building. We went up many flights of steps.

I entered a very brightly lit hall. In the middle of it under a huge lamp stood a chair. There were a few male agents waiting for me as well as "my" female interrogator. I was totally paralysed by this sight. I sat on the chair because they told me to do so. I could not utter a single syllable.

I could not answer any of their questions. My jaws chattered, my teeth rattled, my hands and legs shook uncontrollably. I had turned to jelly. Then I head the order "being her here again tomorrow!"

The wardens took me away and I have not recollection of returning to my cell.

I was under no illusion of what was going to happen next.

A day went by, then another, a week, then a second and I was constantly under the threat and fear of that next day. This lasted until October. I had lost contact with the map. I did not know what was happening in the world. I was totally demoralised. The hunger pangs were unbearable and I suffered from the indescribable anxiety of not knowing when that "tomorrow" would come. I suffered a nervous breakdown.

One morning I woke up and could not get up. I sat on my bed for a long time. I was devoid of all thought. I sat and stared in front of me entirely indifferent to the world around me. I could not remember a single word of Polish. My mind was blank. Then suddenly these words came out of my mouth "Lithuania, my homeland ....." and in that moment my mind came back. From that moment onwards I kept on reciting every poem I knew. And in my thoughts I recalled recently passed years.

Is it really possible to lose your mind so completely?

THAT IS SO DREADFULLY FRIGHTENING!

One night I had a dream, which I can remember to this day :

I dreamt I was in Poland, at home in the lodge which was in the middle of the forest. We had a hectare of farmland next to the garden. I dreamt that beyond the cultivated land, at the edge of the forest a huge army was amassing. The Polish Army was stationed on the other side of the lodge. A group of officers was inside the lodge. We watched the soldiers by the woods closely. They were Germans. One of the officers was walking straight towards us. We were greatly startled by this situation. But I did not forget my manners as hostess and went forward to meet him.

I went towards the gate where we met. Hitler (for it was indeed him) came up to me, shook my hand and said "I will help you."

That is where the dream ended, but the impression of his hand on mine lingered.

I watched autumn approaching through the small chink in the window of our cell. The walks we took in the high walled prison courtyard also helped to identify the seasons. I saw leaves falling from the trees and felt the days getting colder, until finally we felt the first chill of winter. Winter comes early in the Urals. They are already blanketed in snow in October. October came and I was still waiting for "tomorrow" to come.

The Russian woman who was in prison supposedly for not fulfilling her quotas suddenly felt disposed to tell fortunes with her cards. She spread them out and foretold that a road lay before me, a long road, that I would be proven innocent and led to freedom.

She was so certain that this would all come about that she asked me very earnestly to go and see her mother after my release, to tell her that she was alone, as her mother had not had any news about her.

I memorised the address so that if I was released, I could make good my promise and console her poor mother.

And wonder of wonders! That very evening I was called out with instructions to take all my possessions (which were, of course, non existent). This time when we reached the ground floor, the warder led me to the entrance hall. Then into a room to the right of the front doors.

An NKVD clerk sat at the desk opposite the door and along the walls the prisoners from our settlement sat on benches. I recognised father among them.

I had often thought about why father had been arrested. It transpired that when the NKVD agents took the files from the Forestry Commission Office in Białowieża, some "learned" individual (jobsworth) had read in father's file that he spoke German. Naturally to any other, normal person, it would be perfectly obvious that people born and educated in a country under foreign occupation and those who worked under Austrian occupation, whose official language was German, would be fluent in German! However the NKVD judged that the ability to speak German was a crime and arrested father as an enemy of the Soviet Union.

I went up to the desk - and heard the words " you are released" - and then I was given an additional "instruction". I was told never to reveal anything I had seen or heard here to anyone. Then I was given 10 roubles for my journey. I was told to collect my possessions, which had been confiscated during our search, from the NKVD in Karabasz.

"It is not far to the station."

And it was all true. - We were free.

A lightning thought came into my mind. That those playing cards were a trick! I had just sworn not to reveal anything that had happened here and she asked me to tell her mother everything.

The doors to freedom opened at 10pm and we all trooped off to the station. The snow crunched under our feet. We could not stop talking, we had so much to tell each other.

The Siberian railway stations in big towns have huge waiting rooms. Especially on the Vladivostock line.

We went into the waiting room, it was a long and narrow and full of the Red Army. They were all wounded coming back from the front. Some hopped on crutches, others had their arms raised in plaster, outstretched like the wings of an aeroplane, legs in plaster or arms in slings.

It was a nightmarish scenario of war!

They were travelling to Siberia - far from the front lines - for a long period of treatment.

We started to look around us, to try and find some information as to when the next train left for Karabasz. And then, all of a sudden a tall, slim officer in a POLISH UNIFORM, with a POLISH FOUR CORNERED CAP, approached us!

We could not believe our eyes, we never expected to see a Polish Soldier here in the Urals. We went up to him. We told him that we had just been released from prison, that we wanted to reach our families.

At last we had some hews. He told us that the Polish Government in London had signed an agreement with Russia, that General Władysław Sikorski had been to Moscow, that General Władysław Anders had been released from prison and was forming a Polish Army in Russia, that this was the second time the Polish Authorities had demanded the release of Polish prisoners.

Can you imagine that all this information which we had assimilated in one short hour, the joy with which it had filled our exhausted minds and bodies, was as deadly as being arrested and interrogated?

As I left the prison I thought I would go back to the settlement, that I would be set to work again. What other fate could I have envisaged? They could not prove my crime so they let me go.

But as it happened, the reason was quite different, they released me because they had to!

It was an hour of glad tidings, a bright future - it kept going around inn my mind that I did not have to return to the settlement to work for the Soviets, that I would go, as quickly as possible, to find the Polish Army - I wanted to join up so much.

But it was not that easy to get a place on the train, the more agile ones disappeared. Our group got smaller and smaller. After waiting for two days to get a ticker, we too decided to stowaway. We were successful. We were on the train and those 10 roubles had to be our salvation. And this is what happened - we "bought our tickets from the conductor".

The railway line went passed the huts of our settlement. We knew it well and knew that the embankment was not very high, W also knew that the train slowed down when approaching the station. So we decided to jump - it was a successful jump.

It was dark by the time the train approached Karabasz. We could see the lights in some of the windows of the huts. We knew we would be with our families within minutes. At last we got to our hut, father and me. We went in and Mother was waiting for us, praying (she had waited like this every day since the return of the first prisoners.)

After our greetings we told each other everything that had happened, Mother thought that we had died when we did not come back after the first time the Polish Army demanded the release of prisoners, and only a few of those arrested returned. Only the families of those who had not returned, remained in the settlement. The others had already gone to join the army.

That night no-one slept in the settlement.

The NKVD were supposed to organise our transport, which was to take us to where the Polish Army was forming. We were inpatient to leave. At the beginning of December we were told that the wagons were waiting for us at the Station.

Our departure was rapid. We were travelling south. We had no food supplies and had nothing to eat. When the train stopped at one of the stations the authorities informed us that it was to be a two hour stop. We asked if we could go out to buy some food and they gave us permission.

Each family sent one member. When we got back to the station we could not believe our eyes - the train was no longer at the station.

We asked where it had gone - they told us to Tashkent. So we decided to follow our train. We leapt on to the first goods train heading south. The train was already in motion and I bruised my leg very badly as I jumped on to it. In Tashkent we were told that our train had gone off in an unknown direction. We lost all hope of finding out where it had gone. I was feverish and my leg was agonisingly painful.

What were we to do? We decided to go back - but where to? Maybe we would be able to discover the whereabouts of the Polish Army. We were all deadly tired. We travelled on a passenger train which was so crowded that there was no sitting room. We found two empty luggage racks in one compartment which we hastily commandeered. We took it in turns to sleep in them for an hour at a time.

It was in this compartment that we became infested with fleas - the Russian plague! We were very lost and had no idea at all what was to become of us. We were completely powerless.

One of the conductors told us that Poles were gathering in one of the neighbouring collectives. We decided to join them.

A mud hut in Uzbekistan

We were given a mud hut in this collective by the Uzbeks, and the village administrator gave us a few handfuls of flour. However I can't remember how we got there. There were quite a few people in the hut and I was lying on some straw or hay without any covering, my leg was dreadfully painful.

My bruised leg was so painful I could not stand on it. I was just happy to be able to lie down. There were no soothing ointments. Finally the wound burst and the pus started vacating. I bathed the wound in water and gently massaged around it to encourage the pus to come out. For a long time my body had to heal itself - very slowly. This was the end of November or the beginning of December 1941.

We spent Christmas 1941 in this mud hut. And this is where my father found me.

One day I recognised father in the doorway, he had experienced a similar fate to mine. Mother had disappeared into the unknown. Father found out that there was a group of Poles in this collective so came to seek us out. That was how we found each other. I felt a lot safer.

Whilst I was ill I was looked after by the mother of a large family, she fed me. She cooked a handful of the flour we were given by the administrator - it was all she had.

A mud hut - that describes our reality exactly. It is a small hut made of mud, and it is what the Uzbeks live in in their collectives. The floor is also made of mud. Against one of the other walls there is a sort of low shelf also made of mud which serves as a place to sleep - it is about 30-40cm high, strewn with straw - the straw also serves as bedding.

A very basic oven is situated by the door, these are made of wood. The sides of the oven are thick walls of mud. A huge metal pot is cemented into these walls. There is a chimney under which they light a fire.

They cook everything in this pot. Snow is melted for water and they cook soup. If they have any flour the can make a sort of pitta bread which they bake on the outside of the pot.

Another sad Christmas was approaching. On Christmas Eve we decided that we would fast during the day as is the Polish custom on that day. We gave our flour ration to our hosts. Some of our more resourceful friends managed to beg some potatoes and an onion. These priceless items produced potato dumplings and little flatbreads. That night we feasted like kings.

The first star appeared in the Uzbek sky - we sat down to our Christmas Eve feast and sang our first carol.

Some time in January we ran out of fuel. We had to get some more. We burned dry dung, straw and hay. One of our expeditions to get fuel looked like this:

The men went out at night when everyone was asleep. They had previously singled out a haystack. Their journey was difficult, cross country through snow.

When they got there each one of them picked up a sheaf. They were very tired and sat for a while to rest. They lit up their coarse cigarettes and the set off on their way back. When they got back to our mud hut someone notice that the haystack was alight - someone had not stubbed out their cigarette properly.

The haystack burned down due to our carelessness, so we were guilty. We had to make a lightning decision - we had to hide the hay in our bedding and not admit to anything. The hay was hidden, the room swept and everyone lay down to sleep.

Heaven came to our rescue. A thick snowfall obliterated all the footprints. The NKVD could suspect but could not prove who was guilty. We had fuel for quite some time.

The snow and frost were excruciating. We were low on food and fuel. Our bodies were weakened and further tormented by parasites. Flea hunting was a daily past time. But it was impossible to get rid of the nits.

We used to hang our clothes out in the ringing frost in order to freeze the vermin to death.

My leg began to heal. A soon as I was able to get up without help and could walk, we decided to move out and enlist in the army.

Freedom

We set off in search of the Polish Army which was being organised in Russia.

We arrived through various routes at Czok-Pak in Kyrgyzstan where the 8th DP was being formed. The rallying point was next to the station where crowds of people gathered. They all looked like spectres in rags. They all wanted to enlist.

Sadly not everyone was destined to wear the uniform. exhaustion and an epidemic of typhoid decimated the arrivals. Many Polish graves were left behind in Czok-Pak. Only those who were stronger were quarantined and then sent to the site of an old mine where they were issued with uniforms and sent for training.

I walked to the site of an old mine from the rallying point over snow drifts. My feet were wrapped in rags. It was a very tiring march - it was February 1942.

We were given hot food and issued with blankets to cover us.

The women worked in the small hospital, in the office, kitchen and anywhere they were needed.

In order to be issued with a uniform I had to take a "soviet shower". I gave up my civilian clothes which were richly infested with fleas, to be burned.

I came out of the shower dressed in male clothing. Mens underwear, suit and shoes. It was all a little too large, but it was clean and warm!

The only possession which I had left from my civilian life was my prayer book which I had received for my First Holy Communion.

I was happy, - I worked in the office - I had only recently graduated from Business School - I was still a good typist.

Could I have imagined then that in May we would all be free and in Persia?

Our division was ordered to move out in the first wave. We walked to the station. They said it was 10km away - but who know how far it really was. We walked for a very long time. We got to the train deep in the night. The train was overcrowded with soldiers. The news that we were going to Krasnovodzk was passed from lips to lips, across the Caspian Sea - to Pahlavi in Persia.

And that is what happened - BEFORE WE LEFT I THOUGHT ABOUT ALL THOSE POOR SOULS WHO WOULD STAY IN THIS INHUMANE LAND FOREVER - AND BE FORGOTTEN!

When we got to Krasnovodzk a "sea" of people was waiting on the beach for the ship to arrive - they sat on their bundles with fear in their eyes - would there be enough for everyone on the ship? Will anyone be left behind?

We were packed in like sardines on the ship - but it was nothing - this, was not suffering.

The ship sailed - we were so close to being truly free, but the shadow of fear was still upon us.

Somebody died - he did not taste freedom, he remains forever deep in the Caspian Sea. Many were suffering from dysentery and the queues for the toilets were endless, not everyone was able to hang on for hours on end, These are truly macabre memories of scenes which accompanied us to the journeys end.

The ship docked close to Pahlavi, deep in the night. A boat with a POLISH CREW drew up alongside, they brought us a variety of delicacies - dried fruit, chocolate, biscuits!

In the morning we landed on the sandy beach in Pahlavi. The quartermasters were there to greet us, feed us and allocate us to our quarters as free citizens - and we were free, free, FREE!!!

Freedom has no Price

Fortune was with me after I had been quarantined for typhoid. I was accepted into the army. Father's fate was different, he was not yet so old (only 55) but resulting from the trials and hardships suffered in prison, he looked closer to 70. They did not want to accept him into the army. However, the army did feed the civilian population, to which father belonged, from their rations. They received hot meals even though they were not soldiers. The army did not begrudge them anything and shared their rations willingly.

I did not know father had been in touch with Major Ossowski until much later. He advised father to take a few years off his CV and apply to enlist again. If he was successful the major would take him onto his staff at one to work in the office. This time fortune smiled on my poor father and he was accepted into the army.

In June a group of people from our train who had travelled on to a distant collective arrived in Persia. They brought us news of mother and gave us the location of the collective in which she had remained.

Father applied for a pass from his officer and travelled to the collective to find his wife. When he got there she was already in the hospital suffering from such sever exhaustion and malnutrition that she barely recognised anyone. But she did recognise her husband and asked after me. Father returned to his detachment and at the beginning of July news came that she had died.

Persia

Anyone who has read the stories of 1001 nights will be able to imagine our stay in Persia.

Six months in sunny Persia seemed just like those beautiful stories, forever etched on our memories. A hot climate, clean tents and enough food to satisfy us.

From Pahlavi we travelled to the 4th Army Hospital near Tehran. We were taken there by Persian transport, through the mountains; the road often led along the narrow passes where one side fell away into steep ravines. We were enchanted by the stunning countryside.

I shared a tent with Myszka Stankiewicz and Halina Malecha. It was very comfortable and cosy in our tent. Halina was the first to volunteer for hospital training.

We drove to Tehran - it was out first visit there - the view onto the city as we approached was breathtaking. We were back in the realms of 1001 nights - the city looked like one enormous, shimmering mosaic. And the cafés were just like the ones in Poland.

We often organised trips to the city to drink great coffee and eat delicious cakes topped with whipped cream.

There were three Polish camps for civilians close to the city as well as a huge civilian hospital under canvas.

The traffic going through the 4th army camp was incessant, Army units left after a short stay. They left with a song on their lips to go to Iraq where they were trained in the desert. A soon as a unit left another took its place immediately, and then they moved on.

August came and the camp was almost deserted. We received new orders. The second wave of deportees had arrived from Russia.

The sight of these newcomers dimmed the brightness and beauty that was Persia. If you can imagine skeletons walking, these were people, just skin and bones. - THESE WERE OUR FELLOW COUNTRYMEN, POLES RELEASED FROM THE SOVIET PARADISE!

The Shah of Persia converted a newly built school into a Polish Red Cross Hospital, a military hospital. All the employees were to be military - Myszka and I applied to work there.

England sent 600 fully equipped beds. The classrooms were painted white and the beds were covered with red blankets. They were prepared for army transports arriving in August from the USSR. I was transferred from the Department of Civil Matters to begin work in the admissions office of the PRC (Polish Red Cross) hospital.

During our Persian idyll, for that is how I would describe our stay in Persia, we received the tragic, sad news of the horrific murder of Polish Officers in Katyń.

I suffered a severe attack of scurvy. All the wounds on my leg re-opened, my teeth hurt agonisingly. My treatment lasted a long time but thanks to an abundance of fresh fruit, my wounds started to heal. The health giving sunshine was also an added benefit.

In Tehran I also suffered a bout of papatacz. The high fever rendered me helpless. I was admitted onto a hospital ward. After a few days I began to recover and when I woke up one day to find a girl had died in the bed next to mine I fled from the hospital bed assigned to me.

The August arrivals came at all times of the day. The board indicating the number of free beds, filled up rapidly. There was no room on the wards. Patients were laid on mattresses and emergency beds in the corridors and hallways.

The hospital was operational for 24 hours a day. Night time lay waste to the wards. A high percentage of patients who were exhausted by dysentery and other diseases, died. Beds became available for the new arrivals. This continued day after day without any respite.

Doctors and nurses worked unceasingly. Weeks and months went by. Autumn came. There were not so many patients now. Those who recovered re-joined their units. Those who died were buried in the hospitable Persian ground - they had not tasted freedom for long and even if they knew their lives were coming to an end, far from Poland, yet they died peacefully AWAY FROM RUSSIA, at peace because they were FREE, in a FREE COUNTRY!

There is a cemetery in Persia, filled with Polish war graves***, larger than any filled as a result of any battle.

Polish Iranian plaque in the Pahlavi Bandar-e Anzali Polish Cemetery

Entrance to the Polish Cemetery in Pahlavi Bandar-e Anzali - Image courtesy & © of riowang.blogspot - article in English here and Polish here

The Polish Red Cross Hospital with its military staff was converted to a military hospital. The 4th Military Hospital had orders to deploy to Mosul to the 3rd DSK.

We left for Iraq at the beginning of December.

Iraq

The Third Division of Carpathian Rifles (3rd DSK) was stationed in Mosul close to the Turkish border. The Division was made up of the Independent Brigade of Carpathian Rifles which had fought at the battle of Tobruk and was supplemented by the army which had been formed in Russia.

The 4th Military Hospital was stationed in Mosul. Army units underwent intense training. The hospital admitted normal patients. The work was steady, normal. Suddenly this peaceful existence was shattered by dreadful news. An incident occurred in the officer cadet training centre.

It happened during a lecture on landmines - unexpectedly and unbelievably a landmine had exploded - officer Cadet Gigiel shielded his colleagues with his own body. He was invalided for life. He lost both arms and an eye, I had never seen such a mangled body. He was transferred to a British hospital and after his wounds had been treated and he began to recover he was sent to India to be fitted with artificial limbs.

In the springtime Iraq was transformed into a wondrous garden - tulips began to flower and they disappeared as quickly as they had appeared. Cracked earth is all that is left when they're gone.

After six months in Iraq we bade farewell to Mosul and crossed the black Jordanian desert to Palestine.

We travelled in several stages. We spent our nights in British transit camps. The heat at this time of year is unbearable, and we suffered from heat exhaustion.

July 1943

One day when we arrived at one of the staging points we leapt out of the lorries intending to seek some shade when we heard the order - parade!

The flag in the parade ground was lowered to half-mast - something truly awful must have happened!

The officer of the day read out the orders. On the 4th of July 1943, General Władysław Sikorski, the Commander in Chief of the Polish Armed Forces and Prime Minister, had perished in a tragic accident in Gibraltar.

He was a great son of Poland.

PEACE TO HIS MEMORY!

This was a terrible blow - totally unexpected - why now when we needed him so much?

He died in an accident in Gibraltar - who was culpable? WHO WAS RESPONSIBLE FOR THE DEATH OF OUR GENERAL?

He was instrumental in giving us the supreme gift of freedom! "He opened wide the iron gates, he heavy prison doors."

It was he who travelled to the Kremlin and bargained for the release of all Polish prisoners.

It was he who negotiated the release of General Władysław Anders the Commander of the Army in the USSR. He gave over the command of the newly formed Polish Army to him.

THERE ARE NO ADEQUATE WORDS TO DESCRIBE OUR GRATITUDE TO HIM FOR OUR SALVATION!

Palestine

Palestine is another country altogether. It is a welcoming, lush green, sunny place, with orange trees as far as you can see.

There were few patients in the hospital at this time. There was less work. We spent our free time sightseeing.

I met up with father again in Palestine. We visited all the Holy places together, the Basilica in Jerusalem, the Way of the Cross, Golgotha and other Holy monuments. We went to Bethlehem, the birthplace of Our Lord Jesus. All these places made a lasting impression on me.

Every now and again our hospital was moved further south.

The next stage was Gaza. The 5th Border Infantry Division from the Kresy region was stationed there. Our hospital was given over for their used. The Polish Army was moving closer to the front line and the hospitals followed them in tandem.

Egypt

After we left Gaza we were quartered for a short whole in a transit camp. The camp was surrounded by a high wall and sentries stood guard at the gates. Our tent was situated in one corner of the camp.

It was a Sunday. We were given a lift to Cairo - to Groppi's café, for coffee and cakes - we never missed an opportunity like that. We got back that evening so tired that we went to bed immediately. As usual we left a small night lamp burning, which ensured we would have an undisturbed night, with no unwelcome visitors, rats do not like the light.

The night was quiet - too quiet as it turned out! I woke up in the morning and reached out for my uniform, which I had folded next to my bed - it wasn't there, I reached for my shoes which should have been under my bed - I could not find them either. By this time I was wide awake, looked around - and noticed that my friends' uniforms were also missing! I thought it was a prank at first. I woke Myszka who was still sound asleep. Asked her where she had put her uniform - she answered sleepily that it was on the footstool, I asked her where she had put her shoes "I don't know" was the reply, and then she became fully awake. We woke Basia whose uniform and shoes had also disappeared as she confirmed. We came to the conclusion, all of us, that our uniforms had disappeared - but not only these, our handbags were also missing, all we had left were our nightclothes! We had been robbed! By whom? The Arabs.

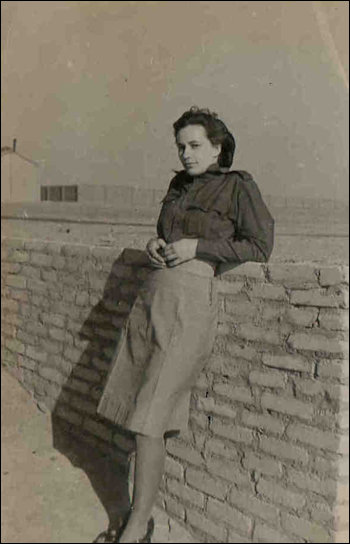

Mother metamorphosises from scrawny undernourished political prisoner to confident army surgical nurse in El-Kasasin, Egypt near the Suez Canal in May 1944

We called the duty officer who informed the commanding officer and we had to wait until new uniforms could be issued from the stores.

The hardest to bear was the loss of our personal possessions - comfortable slippers and all our treasures which were in our handbags, small scissors, lipstick, and other small feminine items.

The hospital was moved to another location, at El Qantara by the Suez Canal. This is where father and I met for the third time, when he was transferred here. It was still 1943.

The hospital at El Qantara was very big. We were expecting wounded as well as other patients. There was a shortage of nurses and it was expected that they would come from Africa from the Polish settlement.

A Polish Red Cross nursing course was organised at the hospital and several of the women office workers volunteered to attend. I was one of them.

Simultaneously with the commencement of our lectures, we went onto the wards for practical training under the watchful eye of the ward sister. As we had volunteered for the training because we wanted to help the suffering, our lectures and practical experience went well.

At the beginning of the course we went onto the ward wearing white aprons and caps. The professional nurses uniforms included shoulder straps with a red cross emblazoned on them and they had a red cross badge on their caps.

Before I took my exams I had to give an injection under the supervision of a sister. This was a daunting experience (truthfully I was petrified!) The sister asked one of her patients who had daily injections if he would consent to my giving him my first injection. He agreed. And I was successful. I stuck the needle in correctly (this was crucial). The patient declared it was no different to any other injection he had received and asked if I could continue giving him his injections. This boosted my morale greatly.

The exams were conducted by a panel of Polish Red Cross members and we all passed. Our colleagues - sisters - prepared a surprise for us. The had prepared shoulder straps for us in secret and obtained our red cross cap badges.

The day after the exams our patients were looking out for us - they knew that if we came onto the ward wearing shoulder straps, we had passed our exams. And that is how we came onto the ward, wearing our shoulder straps.

We began our normal duties, including night duties without supervision. In the new Year the army was preparing for the Italian Front. Our hospital remained in El Qantara.

In May 1944 we heard the news that the 2nd Polish Corps had captured the monastery hill at Monte Cassino. This was truly exhilarating news, but within a few short weeks we witnessed at what cost victory was won at Monte Cassino.

Gravely wounded soldiers arrived at our hospital - they could not return to the front line battleground. Seriously wounded soldiers were brought to the surgical ward. Many soldiers were taken to the psychiatric ward, these poor souls were so traumatised that they had been driven mad by their experiences. It was impossible not feel desperately sorry for them as you walked passed their ward which had to be surrounded by barbed wire.

Soldiers who had contracted tuberculosis at the front were taken to the infectious diseases ward.

The transport of wounded soldiers was brought to Port Said then throughout the night ambulances delivered them to our hospital. The whole of the hospital complex was flood-lit all through the night as the wounded were directed to the various wards. Those on duty moved around carrying lanterns. It was dawn before we were able to get to our beds.

I worked on the surgical ward. I remember many incidents but I will describe three serious ones.

Next morning I got to know my patients. Among them was a second lieutenant who was so badly wounded that he could not control his motions even though he was able to walk. He gave way to despair and decided to commit suicide. Thankfully his colleagues on the ward realised what he was planning to do when he asked them for a razor and his attempt was unsuccessful. He was transferred to an English hospital in Cairo where the conditions were better and which had specialist doctors, unfortunately, he succeeded on his second attempt.

The unhappiest of my patients was a young soldier who fell asleep on guard duty whilst waiting for his relief to arrive. He fell asleep against an open window on the first floor of the guard house. When he fell he damaged his spine and was paralysed from the waist down. He was very young and desperately wanted to live. He asked me constantly if his wounds were healing. When he arrived he was already suffering from advanced bed sores. Both his heels were a mass of wounds which would not heal. The worst of it was that he, too, could not control his motions, he lay on a rubber ring as this was the only way we could ensure his basic hygiene needs. I looked after him for several months but he did not survive.

Next to him was a patient who was in a coma. He never woke up and finally fell asleep forever.

These three and countless others remained forever on Egyptian soil.

One of my patients had a very deep and grave would on his leg which bled frequently. Each time this happened it could have been fatal if he was not given an immediate blood transfusion. During wartime stocks of blood are very hard to come by. The blood bank was in the hospital in Cairo - which was a fair distance away. Our doctors decided to draw up a list of blood donors living on site, just in case. This patients' blood group was compatible with mine and that of my fellow nurses.

One time when I was on night duty, I heard shouting just before dawn. The patient was calling for help. The bleeding was massive. The ward orderly woke the surgical sisters and the surgeon, and I really cannot describe adequately the speed with which events took place. Within minutes the patient was receiving the blood from a direct transfusion from me. The orderly then ran to wake the other nurse whose blood was compatible and so between us we were able to save the life of a young man.

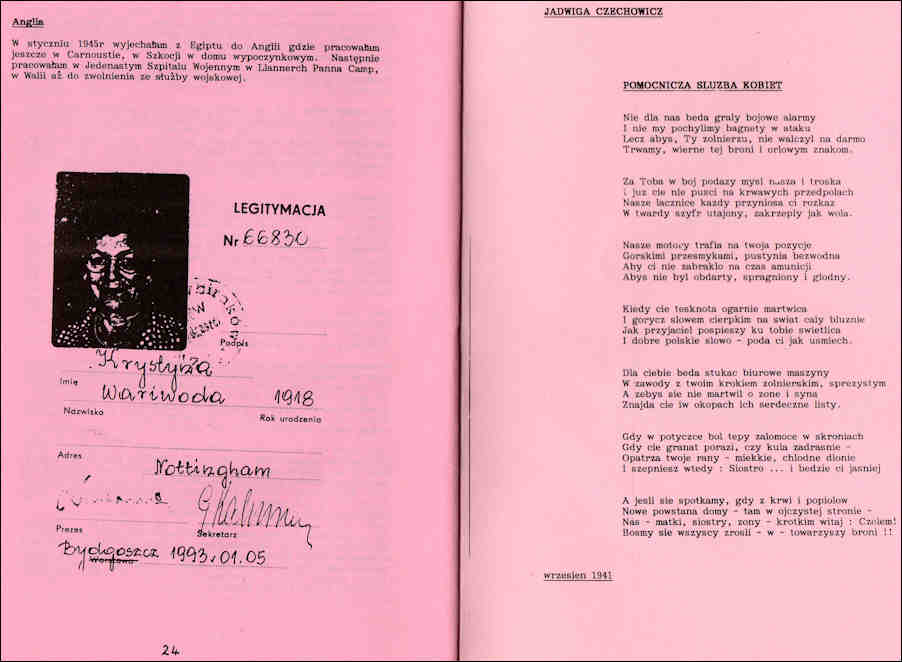

Mother (5 months pregnant with my sister Marysia) and Father at the Lannerch Panna Camp on 20.12.1945 preparing for their first Christmas in the UK as a married couple!

I met my husband in the hospital by the Suez Canal, he had been wounded at Monte Cassino. We were married in November 1944 in El Qantara, and immediately after the ceremony my husband left on a hospital ship for Scotland. He was being transferred to the 1st Army Hospital for further operations. On our wedding day the patient whose life I had saved by giving him my blood, sent us his best wishes via the hospital tannoy system.

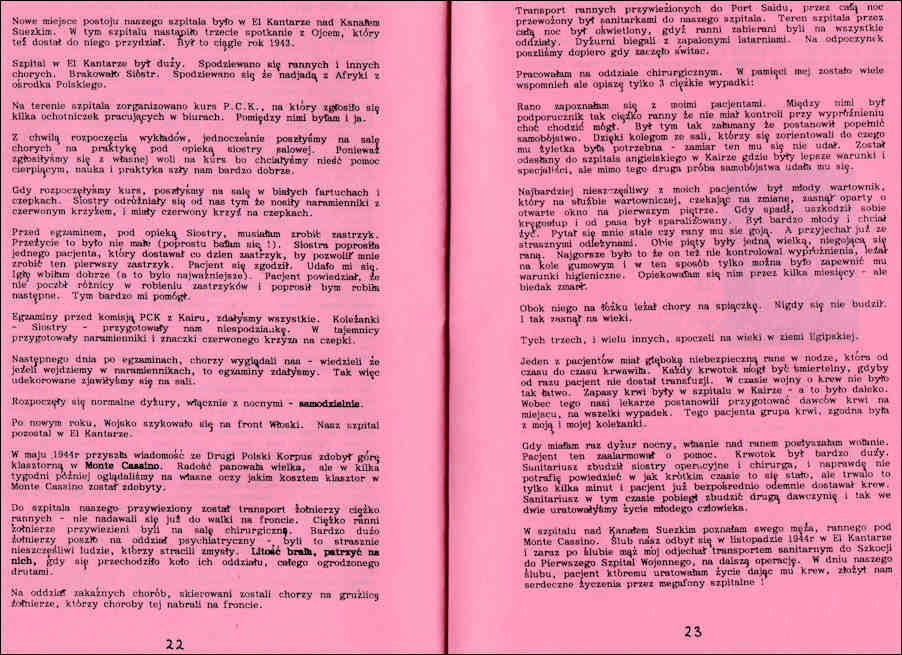

England

In January 1945 I left Egypt for England where I worked in Carnoustie in Scotland in a rehabilitation centre. Then I was transferred to the 11th Army hospital in Llannerch Panna Camp in Wales until I was discharged from military service to start my new life as a wife and soon to be mother of my first child, Marysia born in April 1946. My father lived with us until his death and had the joy of meeting both his granddaughters.

Translation by my sister K Marysia Wariwoda

ADDITIONAL RESEARCHED INFORMATION

Poland in Exile - chronology | Diplomatic Relations with Iran |

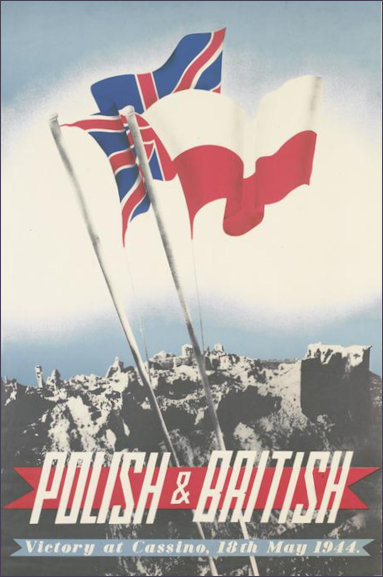

Monte Cassino Commemorative Card (Getty) - 'Postcard commemorating the Polish victory at Monte Cassino in 1944. On the reverse of the card, it states that 'With their British comrades, they (the Poles) were at Narvik, Tobruk, Gazala and they are now in the hills of Italy. They took Monte Casino, Monte Cairo, Piedmonte, Ancona and Pesaro.' (Photo by Michael Nicholson/Corbis via Getty Images)' and the Imperial War Museum (IWM) - 'A depiction of the British Union Flag and the Polish national flag flying next to each other on flagpoles. In the background is a rocky outcrop and a blue sky. text: Polish and British Victory at Cassino, 18th May 1944.

l to r the crowned Polish Eagle (national symbol of freedom when portrayed with a crown) and ribbon and medal of the Virtuti Militari (highest military award) against a backdrop of the monastery at Monte Cassino featuring the national flags of Poland, Great Britain and the United States - image courtesy & © of Getty and the joint flags of Poland and Great Britain against a backdrop of the razed monastery at Monte Cassino with the strapline "Victory at Cassino, 18th May 1944" - image courtesy & © of the Imperial War Museum

* NKVD (precursor to the KGB) the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs.

** Is this what the interrogation centre in Czelabińsk (Chelyabinsk) looked like then and now today?

This is a semi-circular/crescent designed (horse-shoe shaped - mother would have used horse related analogies as opposed to geometrical or celestial descriptions) building in Chelyabinsk confirmed as being built in the 1930s

Map of Chelyabinsk in 1939

l to r - the same building in possibly the late 1930s/early 1940s judging by the shape of the cars and a postcard identifying this building and dating it 1967

Two modern aerial views of the same crescent/semi-circular/horse-shoe shaped building described as "Above the street Vorovskogo "hid" an interesting building" - could this be referring to the activities taking place inside the building as described by my mother?

"Located on the corner of Lenin Avenue and Vorovskogo Street stands the building of the Arbitration Court of the Chelyabinsk region. The semi-circular corner part of the building with a clock (an important attribute of official institutions added at a later stage) faces a busy intersection and Kirov Street." - image courtesy & © of fotki.yandex.ru - so still an 'administration' building then?

*** Polish cemetery in Pahlavi (now Bandar-e Anzali) | Very enlightened and well structured article on the anomaly of a Cemetery on the banks of the Caspian Sea (available in Polish and English) by riowang.blogspot

An Omen? Chelyabinsk Meteorite February 2013 - The Chelyabinsk meteor was a superbolide caused by an approximately 20-metre near-Earth asteroid that entered Earth's atmosphere over Russia on 15 February 2013 at about 09:20 YEKT, with a speed of 19.16 ± 0.15 kilometres per second.

Images courtesy of Alex Alishevskikh and earthsky.org - a whimsical thought, maybe this was the spirit of my mother returning to the scene of her incarceration and giving a two-fingered salute to her tormentors.

Page updated : 12th April 2017