Return to Book 9

Les Filles du Roi - The King's Daughters

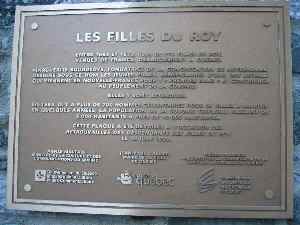

"De 1663 à 1673, quelques 800 demoiselles sont venues de France prendre part au peuplement de la vallée du St-Laurent. Elles ont assuré la survie de la Nouvelle-France par leur fécondité légendaire en donnant naissance à la race des Canadiens-Français. Appelées Filles du Roy parce que les dépenses liées à leur transport et à leur établissement ont été assumées par le trésor royal, cette population féminine a représenté près de la moitié des femmes qui ont traversé l’Atlantique en 150 ans."

Between 1663 to 1673, some 800 young ladies from France to settle in the St. Lawrence Valley. Their arrival ensured the survival of New France and the emergence of the French-Canadian colonialisation programme. Called 'The King's Daughters' because the expenses related to their travel and settlement costs were assumed by the royal treasury. This specific group of women accounted for almost half of the female population who crossed the Atlantic over 150 years.

Introduction

We are introduced to the concept of 'The King's Daughters', for the first time in Angélique and the Demon although we'll come across these girls in further volumes throughout the remainder of the series. Marguerite Bourgeoys was instrumental in looking after these girls as well as her own nunnery sisters.

'St. Marguerite became the official guardian to the “filles du roi”, young orphan girls sent by the monarch to establish new families. She lodged them in her own home, served as a matchmaker, and prepared them for their new life as pioneers. Her signature appears as a witness on many of the early marriage contracts in Montreal. As a result of these activities she was affectionately referred to as “the Mother of the Colony”. '

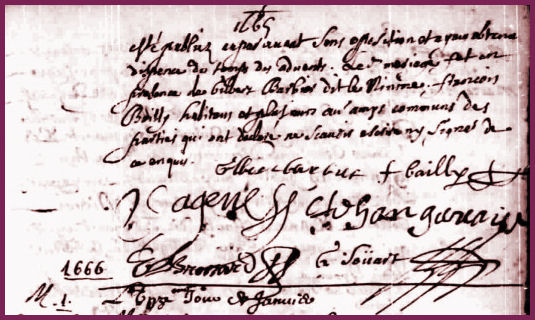

An example of a marriage certificate dated 1666

About 'The King's daughters'

[Source: King's Daughters and Founding Mothers: The Filles du Roi, 1663-1673 by Peter J. Gagné. Pawtucket, RI: Quinton Publications, 2001. pp 15-42]

Between 1663 and 1673, 768 Filles du Roi or "King's Daughters" emigrated to New France under the sponsorship of the French government as part of the overall strategy of strengthening the colony until it could stand on its own without economic and military dependence on France.

In 1663, about 2,500 colonists lived in New France, for the most part on the north shore of the Saint Lawrence between Québec and Montréal. With a constant threat from the Iroquois and the more populous English colonies on the Atlantic coast, the need to populate New France became a growing concern for Louis XIV and his colonial advisors. Through the early 1670s however, men of marriageable age far outnumbered the women of marriageable age. Unable to find a wife in Québec, a great number of male immigrants returned to France after their three-year term of service expired.

In 1663, about 2,500 colonists lived in New France, for the most part on the north shore of the Saint Lawrence between Québec and Montréal. With a constant threat from the Iroquois and the more populous English colonies on the Atlantic coast, the need to populate New France became a growing concern for Louis XIV and his colonial advisors. Through the early 1670s however, men of marriageable age far outnumbered the women of marriageable age. Unable to find a wife in Québec, a great number of male immigrants returned to France after their three-year term of service expired.

Between 1634 and August 1663, while the colony was governed by the Compagnie des Cent Associés, about 262 filles à marier (marriageable girls) were recruited by individuals or by private religious groups who paid their travel expenses and provided for their lodging until they were married. But individual recruiters and private organizations had little success in enticing single women to emigrate to New France, and fewer than ten filles arrived in the colony in most years. In 1663, the King took over direct control of the government of New France and initiated an organized system of recruiting and transporting marriageable women to the colony. On September 22, 1663, thirty-six girls --the first group of Filles du Roi-- arrived in Québec.

The recruiting of Filles du Roi took place largely in Paris, Rouen and other northern cities by merchants and ship outfitters. A screening process required each girl to present her birth certificate and a recommendation from her parish priest or local magistrate stating that she was free to marry. It was necessary that the girls be of appropriate age for giving birth and that "they be healthy and strong for country work, or that they at least have some aptitude for household chores."

The cost of sending each Fille du Roi to New France was 100 livres: 10 for the recruitment, 30 for clothing and 60 for the crossing itself --the total being roughly equivalent to $1,425 in the year 2000. In addition to having the costs of her passage paid by the state, each girl received an assortment of practical items in a case: a coiffe, bonnet, taffeta handkerchief, pair of stockings, pair of gloves, ribbon, four shoelaces, white thread, 100 needles, 1,000 pins, a comb, pair of scissors, two knives and two livres in cash. Upon arrival, the Filles received suitable clothing and some provisions.

All of the Filles du Roi first landed at Québec City where 560 remained, with 133 being sent to Montréal and 75 to Trois-Rivières.

While awaiting marriage, they were lodged in houses in dormitory-style settings under the care of a female chaperone or directress where they were taught practical skills and chores to help them in their future household duties. Suitors would come to the house to make their selection, and the directress would oversee the encounters.

When selecting a Fille du Roi, the suitor looked beyond outward appearances and considered the practical attributes of a bride that would be adapted or disposed to the rigours of the colony. The preference seems to have been for peasant girls because they were healthy and industrious, as opposed to city girls who were often considered lightheaded and lazy. Marie de l'Incarnation, mother superior of the Ursuline convent at Québec City and one of Québec's early female founders, requested in 1668: "From now on, we only want to ask for village girls who are as fit for work as men, experience having shown that those who are not raised [in the country] are not fit for this country."

Great excitement accompanied each new arrival of the King's Daughters and the quays were full of spectators, family members and prospective suitors.

Every Fille du Roi had the right to refuse any marriage offer that was presented. In order to make an informed decision to accept a would-be husband, the girls asked questions about the suitor's home, finances, land and profession.

Every Fille du Roi had the right to refuse any marriage offer that was presented. In order to make an informed decision to accept a would-be husband, the girls asked questions about the suitor's home, finances, land and profession.

Having a home of one's own was one of the most important considerations for a Fille du Roi. According to Marie de l'Incarnation, "The smartest [among the suitors] began making an habitation one year before getting married, because those with an habitation find a wife easier. It's the first thing that the girls ask about, wisely at that, since those who are not established suffer greatly before being comfortable." After agreeing to marry, the couple appeared in front of a notary to have a marriage contract drawn up, and the wedding ceremony generally followed within 30 days. For the Filles du Roi, the average interval between arrival and marriage was four to five months, although the average interval for girls aged 13 to 16 was slightly longer than fifteen months.

In addition to any dowry of goods that the bride may have brought with her from France, each couple was given an assortment of livestock and goods to start them off in married life: a pair of chickens and pigs, an ox, a cow and two barrels of salted meat. The King's Gift of 50 livres is believed to have been a customary addition to the dowry, but only 250 out of 606 known marriage contracts make reference to an additional dowry given by the King. Once married, there was an incentive to have large families. A yearly pension of 300 livres was granted to families with ten children, rising to 400 livres for 12 children and more for larger families.

In November 1671, Intendant Jean Talon in a letter to the King wrote that the birth of six to seven hundred babies that year confirmed the fertility of the country. He predicted that "without further help from the girls from France, this country will produce more than one hundred marriages in the first few years and many more after that, as time goes by." Talon advised that it would not be necessary to send more girls the next year in order for the colonists to more easily give their daughters in marriage.

In 1672 France and England declared war on the Dutch republic, requiring a great deal of the attention and finances of the French government. The French authorities decided it was too costly to continue sending Filles du Roi and unnecessary since the colony's own population could provide a sufficient number of marriageable women. In September 1673 the last shipment of Filles du Roi arrived from France, and the program ended. The population of New France had risen to 6,700 people, an increase of 168% in the eleven years since the program had begun. Although the Filles du Roi represent only 8% of the total immigrants to Canada under the French régime, they account for nearly half of the women who immigrated to Canada in the colony's 150-year history.

More information can be found at Richard Nelson.org

Canada 21st Century

Canada recognises and commemorates the arrival of these pioneer women.

The filles du roi, or King's Daughters, were some 770 women who arrived in the colony of New France (Canada) between 1663 and 1673, under the financial sponsorship of King Louis XIV of France. Most were single French women and many were orphans. Their transportation to Canada and settlement in the colony were paid for by the King. Some were given a royal gift of a dowry of 50 livres for their marriage to one of the many unmarried male colonists in Canada. These gifts are reflected in some of the marriage contracts entered into by the filles du roi at the time of their first marriages.

The filles du roi were part of King Louis XIV's program to promote the settlement of his colony in Canada. Some 737 of these women married and the resultant population explosion gave rise to the success of the colony. Most of the millions of people of French Canadian descent today, both in Quebec and the rest of Canada and the USA (and beyond!), are descendants of one or more of these courageous women of the 17th century.

"Mothers of the Quebec Nation" / "Mères de la nation québécoise"

Re-enactment and historical group

The re-enactment group showing us how it could have looked to the awaiting colonists all those centuries ago.

Return to Top / Angélique Home Page / Home Page

Page updated : 11th January 2017