A Terrible Splendour

A Terrible Splendour by Marshall Jon Fisher

From the Wall Street Journal by Jay Jennings - Sub-title : Gottfried von Cramm - the biography of the persecution years

(Read my review here)

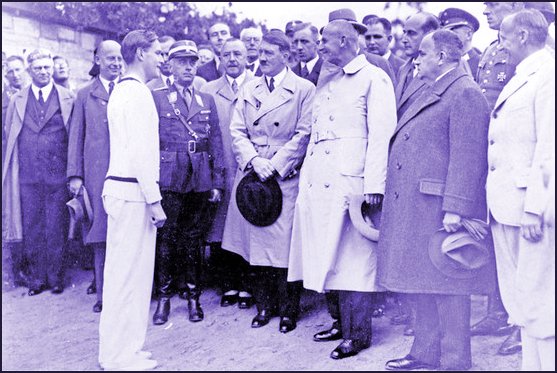

From the Granger Collection : Cramm and Adolf Hitler meet in 1933

Playing in the Dark

In 1937, an epic tennis match unfolded as the Nazi storm gathered.

As was true every year since Wimbledon's tennis stadium was built in 1922, the grass at Centre Court in the summer of 1937 had been worn to brown patches at the baseline and service line during tournament play. Players started, stopped and skidded hundreds of times during matches, and the grass could have used a break to recover after the Wimbledon championships ended in early July. Two weeks later, though, on July 20, the players who had faced each other in the final there were back again. Don Budge, a 22-year-old American, and Baron Gottfried von Cramm of Germany, 28, were scheduled to meet in the sport's premiere team competition, the Davis Cup.

Budge and Cramm were competing in what was essentially a semifinal to determine whether the U.S. or Germany would go to the challenge-round final against England. The match normally would have been staged on Court No. 1, but in a tribute to the renown of the two players, Wimbledon officials moved it to Centre Court. The American star, who had honed his serve and backhand to almost untouchable sharpness, made a likely favorite for the British, since he was taking on the representative of the increasingly bellicose German nation. But the crowd was on Cramm's side: England was already set to play in the final round, and the fans were hoping that the Germans would beat the formidable American team, giving England a better shot at the cup.

Cramm had other supporters that July day, but their backing sent a chill through him: Nazi officials sitting in the royal box expected him to win for the glory of the fatherland. A victory would also reassure them about his patriotism. The German star had refused to join the Nazi Party, and in April he had been interrogated by the Gestapo regarding allegations of homosexual activity -- a crime in Nazi Germany. The handsome, aristocratic Baron von Cramm desperately needed to redeem himself against the homely young American who had learned to play tennis on public courts in California. Cramm's prospects were not encouraging: In the Wimbledon final, Budge had beaten him easily in straight sets.

But then the match began, and spectators and players alike soon realized that an extraordinary competition of skill and guile and endurance was under way. James Thurber, the tennis-besotted writer for The New Yorker magazine was on hand, and he would later describe the Budge-Cramm five-set marathon as "the greatest match in the history of the world."

The case for the greatest match or game or championship ever played -- that staple of bar arguments -- inevitably has to be based on something more than simple drama on the field, court, course or ice. The confrontation between two opponents should also speak in a larger way about the world at that moment. A lot of tennis has been played since 1937 -- and for pure athletic drama, nothing could top the 1980 Wimbledon final between Bjorn Borg and John McEnroe -- but in Marshall Jon Fisher's rich and rewarding "A Terrible Splendor," he makes a strong claim to greatest-ever status for Budge vs. Cramm in the Davis Cup.

Nowadays the Davis Cup has become a largely marginalized but patriotically required nuisance to the already overloaded tennis pro. But back in the 1930s it was a major international sports event, on a par with a heavyweight title bout. In addition to the English fans' self-interested rooting for Germany to knock off the U.S., they brought an affection for Cramm himself to the match. He was a two-time loser in the Wimbledon finals but had displayed such impeccable sportsmanship and style that he had earned the title "the Gentleman of Wimbledon."

Further endearing Cramm to the crowd was his underdog status against Budge, the best player of his day. Budge played a transcendently beautiful brand of tennis -- Mr. Fisher calls it an "unassailable package of power and consistency that many would consider the finest ever even seven decades later." Armed with the game's best backhand, Budge struck the shot so hard that one opponent said, after encountering it at the net, that "you'd swear you were volleying a piano."

Cramm's story provides the emotional ballast of "A Terrible Splendor." In contrast to Budge, whose father was a truck driver, Cramm was a dashing blond member of the German aristocracy, single-mindedly pursuing the game on the court of the family's summer castle and later at Berlin's exclusive Rot-Weiss Club. "Every year that von Cramm steps onto the Centre Court at Wimbledon," reported one observer, "a few hundred young women sit a little straighter and forget about their escorts."

That the young women's interest was in vain was Cramm's secret. His rise to the top of German tennis during the 1930s, just as the Nazis tightened their grip on power, corresponded with the player's dawning realization of his homosexuality -- a proclivity that the Nazis increasingly criminalized. Much of the tension in "A Terrible Splendor," aside from the white-knuckle Davis Cup match, derives from Cramm's attempt to live and compete under Nazi suspicion. On that prewar afternoon at Wimbledon, while Nazi officials were sipping tea with British royalty, Cramm's value as a propaganda tool for Aryan supremacy was being weighed against his liability as a homosexual. As long as Cramm atoned for his Wimbledon loss by winning in this Davis Cup match, Mr. Fisher implies, the German would be spared persecution. Much more than a trophy was at stake.

In addition to the two on-court competitors, a third player looms large in "A Terrible Splendor": Bill Tilden, a tennis superstar of the 1920s who had done much to popularize the sport in America but who had also long feuded with the tennis bureaucracy in the U.S. The American tennis establishment, Mr. Fisher says, was leery of Tilden's off-court flamboyance and rumors about his sexual tendencies. (In the 1940s, Tilden was jailed twice on morals charges involving teenage boys.) In 1937, Tilden was unofficially coaching the German team, having been rebuffed by the Americans.

To this overarching narrative, Mr. Fisher brings a sharp eye for detail. He vividly sketches the anything-goes atmosphere of Weimar Berlin -- the book's fascinating photographs even include one of transvestites at a Berlin nightclub where Cramm met a Jewish actor who became his lover, further endangering the tennis player's fortunes in Nazi Germany.

Mr. Fisher's research has also turned up details that tennis fans will savor. We learn, for instance, that Budge used a "Ghost" model racket that the Wilson sporting-goods company designed specifically for him. It was "a substantial weapon, heavier and with a bigger handle than anyone else's," Mr. Fisher writes. The racket's grip was "combed basswood," just like the one Bill Tilden preferred, rather than the leather wrap that had been adopted by most players. We also learn that a five-set tennis match back then was even more grueling than it is today. Players didn't get a break between every other game, as by modern convention; they got a 10-minute intermission only between the third and fourth sets. Thus, fans were afforded long stretches of continuous play.

One hurdle Mr. Fisher faced in writing "A Terrible Splendor" is that in the titanic confrontation between Don Budge and Gottfried von Cramm, he didn't have two captivating subjects: Budge, however scintillating his tennis might have been, is not a dramatic character. Cramm claims our interest at every turn. No doubt the imbalance is one reason why the author lavishes attention on Tilden, who in truth was a minor factor in the story.

Though Mr. Fisher makes note of "the hyperbole of the day," he occasionally succumbs to it himself -- referring to a tennis match as "an ulcer-inducing cascade of tight moments" might cause readers to reach for the Pepto-Bismol. The author also indulges a little too freely in satisfying his "need to dramatize," as he says, "without knowing for certain exactly what was said or thought." To that end, he presumes a romantic attraction between Tilden and Cramm -- a speculative theme that is simply jarring.

As for the tennis in "A Terrible Splendor," Mr. Fisher spaces out his account of the Davis Cup match, dipping in and out of it as the book moves along. Each of the five sets is given its own chapter, which undermines the momentum of the play as Budge and Cramm battle back and forth. But the account of the action is gripping. Cramm initially goes up two sets, 8-6, 7-5. "He attacked incessantly," Budge said later of his opponent, "and kept me on the run." The American finds his serve in the third set, winning 6-4. Down two breaks in the fourth, Cramm lets up, saving his strength for the fifth, and loses 6-2. NBC radio cancels its programs to stay with the match until the end.

In the stadium, the largely British crowd chants "Deutschland! Deutschland!" as Cramm takes a 3-1 lead in the fifth -- but then Budge storms back. A reporter for the New York Herald Tribune will write that the players were hitting winners "off balls that themselves appeared to be certain winners." James Thurber called the display by both players "physical genius." But someone had to win, and, in the end, Budge prevailed.

"A year later," Mr. Fisher writes in the long final chapter, "Gottfried Cramm was in prison." Here we learn about the postmatch fates of the characters we've met, and as many intriguing storylines emerge as in what has gone before. This is especially true of Cramm: He was imprisoned for "deviant" behavior, released after a few months, drafted into military service and eventually sent to the Russian front after war breaks out. Remarkably, he survives -- and, perhaps even more remarkably, goes on in the 1950s to marry the American heiress to the Woolworth fortune, Barbara Hutton. Troubled by addiction and depression, Hutton had also long nursed an obsession with the dashing German. A friend observed that Cramm "didn't really want to marry her but thought that he could help her."

On the evidence of "A Terrible Splendor," that appraisal is entirely believable. In a life filled with glory and hardship, Cramm seems to have conducted himself unfailingly with honor and sportsmanship. His depiction by Mr. Fisher is a fitting tribute.

Mr. Jennings, a former features editor at Tennis magazine, is the editor of the literary anthology "Tennis and the Meaning of Life."

Page refreshed : 12th June 2017