Tennis and the Titanic

Home Page / Back to Tennis TitBits / Back to Tennis Home Page

Read my review of the book here

From the Daily Mail

The incredible story of two Titanic survivors and tennis icons - including one who refused to have frostbitten legs amputated and won U.S. Open twice.

PUBLISHED: 04:07, 13 March 2012 | UPDATED: 10:14, 13 March 2012

As the RMS Titanic makes a second run to the big screen next month, little is said about two athletes who survived the tragedy and went on to dominate professional tennis. Richard Norris Williams and Karl Behr were among the best of the best in the tennis world - and their lives were thrown into disarray when the 'unsinkable' ship met its end in 1912. Behr was a 26-year-old Yale graduate when he boarded the Titanic, mostly in pursuit of his future wife, Helen Newsom.

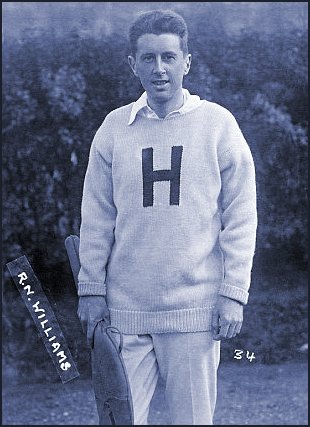

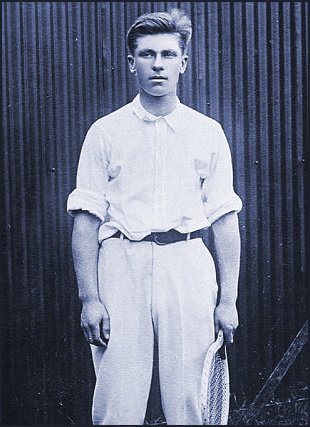

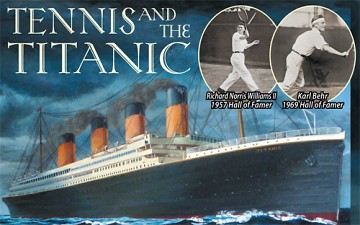

A lot in common: Richard Norris Williams, left, and Karl Behr, right, were both both highly ranked American tennis players who also survived the 1912 Titanic disaster. After the massive ship hit an iceberg on that fateful night, Behr was offered the chance to get out early with Newsom as they boarded lifeboat No. 5 - the second boat to escape.

It was widely reported that Mr Behr proposed to Newsom in the lifeboat that carried them away from the doomed vessel. The couple were married about a year later - in March 1913.

Between 1906 and 1915, Behr was ranked in the U.S. top ten seven times - reaching No. 3 in 1914. He died in 1949, and was posthumously inducted into the Tennis Hall of Fame in 1969.

Richard Williams was 21 when he boarded the Titanic with his father on his way to the US Championships at Newport before entering Harvard in 1912. His father was reportedly crushed to death one of the Titanic’s smoke stacks as the ship split in two.

Despite being waist-deep in the freezing waters of the Atlantic Ocean, Williams survived and was taken aboard the RMS Carpathia, the steamship made famous for plucking hundreds of Titanic passengers to safety. A doctor offered to amputate Williams’ badly frozen limbs, but Williams rejected the doctor’s recommendation. Williams went on to reach the quarter finals of the U.S. Open just months later, and won the tournament in 1914 and 1916. He also won the Wimbledon title in 1920 and achieved a gold medal at the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris.

In 1957, Williams was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame. This week, their story will be put on display during a presentation by tennis memorabilia collector Robert Fuller at The Pavilions of Harrogate Antiques & Fine Art Fair in Great Britain.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Tennis and the Titanic from the International Tennis Hall of Fame

(Another exhibition devoted to tennis)

Like many of the R.M.S. Titanic’s approximately 2,200 passengers, Americans Karl Howell Behr and Richard  Norris Williams II climbed aboard the ill-fated ship in search of their dreams—Behr was chasing love, and Williams striving for an Ivy League education and a successful tennis career. When the grand, “unsinkable” ship struck an iceberg late on April 14, 1912, the two were among the small, fortunate group of just 700 or so survivors. After meeting for the first time aboard the rescue ship R.M.S. Carpathia, neither man took their good fortune for granted, and they achieved great success as two of the best players in the history of tennis.

Norris Williams II climbed aboard the ill-fated ship in search of their dreams—Behr was chasing love, and Williams striving for an Ivy League education and a successful tennis career. When the grand, “unsinkable” ship struck an iceberg late on April 14, 1912, the two were among the small, fortunate group of just 700 or so survivors. After meeting for the first time aboard the rescue ship R.M.S. Carpathia, neither man took their good fortune for granted, and they achieved great success as two of the best players in the history of tennis.

Williams remarkably won the U.S. Nationals Mixed Doubles title just months after the Titanic disaster, and went on to capture several other major titles, and he was honoured for his achievements with Hall of Fame induction in 1957. Behr, who was already an established player before the ship’s voyage, was ranked within the top-5 in the nation, and was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1969.

As the world commemorates the 100th anniversary of the Titanic disaster, the International Tennis Hall of Fame & Museum in Newport, R.I. will pay tribute to these two remarkable survivors with a special exhibit in their honour, Tennis and the Titanic, opening on April 12.

“This has been a fascinating exhibit to develop. Our goal was to shed light on the interesting lives of two remarkable men who survived one of the most infamous catastrophes in modern history, but were able to go on to have elite careers as athletes and success in other areas of life,” said Doug Stark, museum director at the International Tennis Hall of Fame & Museum. “We are grateful to the Behr and Williams families for their support in developing this exhibit. We look forward to welcoming them to the exhibit opening, which will offer a unique opportunity to hear more about Titanic survivors and Hall of Fame tennis players Richard Norris Williams II and Karl Howell Behr from the people who knew them best.”

Tennis and the Titanic will feature dynamic imagery and narratives detailing Williams’ and Behr’s lives before, during, and after the ship’s sinking. In addition, it will feature various personal mementos as well as artifacts from their tennis careers. Highlights of the exhibit include personal letters that were in the pocket of Williams’ fur coat when he jumped overboard, on loan from the Williams Family and a rare photo of the two tennis greats together. Tennis memorabilia featured includes Williams 1914 U.S. Nationals Men’s Singles Championship trophy, which he won at Newport, where the event was played before moving to New York and becoming known as the US Open. In addition, his 1920 Wimbledon Men’s Doubles Championship trophy and an old-fashion racquet press that he used to carry his gear to tournaments worldwide, will be displayed.

American Richard Norris Williams II had been living in Europe and preparing for a collegiate tennis career at Harvard when he boarded the Titanic with his father. When they felt the collision with the iceberg, they believed there was some trouble but did not imagine the situation to be as dire as it turned out. The pair helped people board lifeboats, and worked out in the gym to pass time and stay warm. When they realized the ship was close to sinking, the men readied themselves to jump in the water. It was, however, too late, and at that moment the four massive funnels came crashing down and one crushed Williams’ father.

American Richard Norris Williams II had been living in Europe and preparing for a collegiate tennis career at Harvard when he boarded the Titanic with his father. When they felt the collision with the iceberg, they believed there was some trouble but did not imagine the situation to be as dire as it turned out. The pair helped people board lifeboats, and worked out in the gym to pass time and stay warm. When they realized the ship was close to sinking, the men readied themselves to jump in the water. It was, however, too late, and at that moment the four massive funnels came crashing down and one crushed Williams’ father.

With no time to mourn his father, Williams jumped into the icy water and clung to a lifeboat for hours in frigid water. After he was saved, Williams realized that he had no feeling in his legs, and when he tried to stand or walk, the pain was unbearable. Doctors aboard Carpathia recommended his legs be amputated. Williams, however, was not willing to give up his dreams for a successful tennis career. To avoid amputation, he spent hours walking the decks to get the feeling back and save his legs.

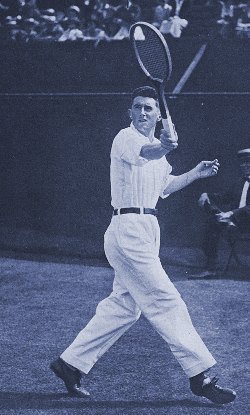

Williams’ perseverance served him well. He went on to play at Harvard, and ultimately achieved a world ranking of No. 4 and a U.S. ranking of No. 1. Remarkably, Williams won the U.S. Nationals Mixed Doubles with Mary Browne just months after the disaster, and later won an Olympic Gold in mixed doubles with Hazel Hotchkiss Wightman. In all, he won a total of six major championships and was a member of five triumphant Davis Cup teams.

In a real life story that could be the basis for a movie, Karl Howell Behr, a dashing, successful businessman and established tennis player claimed it was a business trip to Europe that required him to be on theTitanic’s maiden voyage. In reality, he boarded Titanic to follow Helen Newsom, the woman he loved, but whose parents did not approve of him. After the ship struck the iceberg, Helen and her parents were hastily put into one of the first life boats. While the call was for “women and children only,” Behr was convinced to climb aboard to help row the  boat.

boat.

Aside from the survivor’s guilt that plagued him all his life, Behr came away unscathed. Once aboard the rescue ship Carpathia, Behr became part of the Survivor Committee, helping to organize and assist the survivors. His role was appreciated by the survivors, and through the catastrophe, he also inadvertently proved himself worthy to Helen’s parents; the two were married in March 1913.

Prior to the Titanic disaster, Behr had a thriving tennis career, having been a doubles finalist at Wimbledon and a finalist at the U.S. Nationals, as well as playing on the U.S. Davis Cup. After surviving the ship, he continued to play competitively, achieving a career high ranking of No. 3 in the United States.

Williams’ and Behr’s first meeting was aboard the Carpathia. Prior to their encounter, Williams was an aspiring tennis player who had closely followed Behr’s tennis accomplishments. Two years after the Titanic disaster, in 1914, Williams was en route to his first U.S. National Championship in singles, when he came across a familiar face on the other side of the net at the tournament, which was hosted at the Newport Casino, now home to the International Tennis Hall of Fame & Museum. Williams’ quarterfinal opponent was Karl Behr, whom he beat in straight sets 6-2, 6-2, 7-5. The men played against each other a few others times in their careers and remained friendly, bound forever by their harrowing experience and their love of the game.

Tennis and the Titanic will be on display for approximately one-year in the Woolard Family Enshrinement Gallery at the International Tennis Hall of Fame & Museum in Newport, R.I. The International Tennis Hall of Fame & Museum is a non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the history of tennis and honouring its greatest champions and contributors. Induction to the International Tennis Hall of Fame is based on the sum of one’s achievements and accomplishments in tennis and is the highest honour a player or leader in the sport can receive. Since 1955, the International Tennis Hall of Fame has inducted 220 people from 19 countries.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Titanic’s Tennis Star Survivors

From History.com

Tennis Hall of Famers Dick Williams and Karl Behr will be forever linked in history, but not just because of their on-court exploits. One hundred years ago, both tennis stars survived the most famous shipwreck in history.

The 1,500 tennis fans packed into the grandstand showered applause upon Karl Behr and Dick Williams after their thrilling fourth-round match in the 1912 Longwood Challenge Bowl. Old-timers agreed that the match had been the finest in the tournament’s history. For five sets on a warm July afternoon, Behr and Williams shared the same grassy rectangle, but the men already shared a much stronger bond—one forged in ice. Just 12 weeks prior, the two future tennis Hall of Famers had both survived Titanic’s sinking.

Both Behr and Williams were chasing their dreams when they separately ascended Titanic’s gangway in Cherbourg, France. The 26-year-old Behr had been a tennis standout at Yale, and in 1907 he was a doubles finalist at Wimbledon and a member of the U.S. Davis Cup team. As he boarded Titanic, however, Behr had more important things than tennis on his mind, mainly 19-year-old Helen Newsom.

The tennis star had been pursuing his sister’s classmate, but Newsom’s mother and stepfather disapproved of the age gap between the suitors and hoped a European trip might cool the romance. Behr, however, concocted a business trip to Europe and followed along. When Newsom telegrammed Behr in Berlin to say she was sailing home aboard Titanic, he quickly booked a ticket on the giant ocean liner to surprise her.

While Behr was on the downside of his tennis career, Williams was just beginning his. The 21-year-old descendant of Ben Franklin had American blood in his veins, but he was born and raised in Europe. His trip to America to play the summer tennis circuit before matriculating at Harvard had been delayed by a case of the measles, but it left him with the seeming good fortune of sailing with his father, Charles, on Titanic’s historic maiden voyage.

Williams and his father dined at the table of Captain Edward Smith on April 14, 1912, before retiring for the night. Shortly before midnight, the pair was awoken by the collision with the iceberg. Charles Williams was not worried initially. Decades earlier, he had been aboard a ship that struck an Atlantic iceberg, and the gash had simply been plugged with the boat’s cotton cargo. Father and son donned life vests underneath their raccoon coats and tried to remain warm by walking the deck and riding stationary bikes in the exercise room.

Behr, who had been awake when the collision occurred, roused Newsom and her mother and stepfather from sleep. When the situation turned dire, the party jumped into a lifeboat and watched in horror as Titanic began to sink into the sea. Back on deck, Williams turned to his father and yelled, “Quick! Jump!” Just at that moment, however, an enormous smokestack crashed down and instantly crushed Charles Williams to death. It narrowly missed Dick Williams, who plunged into the 28-degree water. He swam furiously to a collapsible lifeboat that he would cling to for hours before he, Behr and 700 other survivors were rescued by RMS Carpathia.

When the exhausted Williams was pulled from the icy waters, he was suffering from hypothermia and his legs were a worrisome shade of purple. A doctor on board recommended amputation to prevent the onset of gangrene, but Williams refused. “I’m going to need these legs,” he reportedly said. Throughout the trip to New York, Williams walked the deck every two hours, even through the night, to restore his circulation. It worked, and within weeks he was back swinging his wooden racket.

It was on board Carpathia that Behr first met Williams, and three months later they squared off on the finely manicured lawns of the Longwood Cricket Club near Boston. Williams, the boy wonder, had an incredible summer, winning the national clay court championship, the national mixed doubles championship and the Pennsylvania state championship.

At Longwood, the phenom initially overpowered Behr with his athleticism, blanking the veteran in the first set and winning the second 9-7. The savvy Behr, however, made the adjustments to capture the next three sets and a 0-6, 7-9, 6-2, 6-1, 6-4 victory. The Boston Globe reported the next day that “if one of the 1,500 spectators went away dissatisfied, he was indeed hard to please.”

The two men competed again a few weeks later in Long Island, and they met in the quarterfinals of the 1914 U.S. Championships (today’s U.S. Open). Williams won easily in straight sets en route to the first of his two national titles. Before his career was over, Williams would be a member of five winning Davis Cup teams and capture a Wimbledon doubles title, two U.S. doubles championships and a mixed doubles gold medal in the 1924 Olympics.

While Williams lost his father and nearly his legs in the Titanic disaster, it was Behr who struggled more in its aftermath. He was plagued by survivor’s guilt and in 1917 had an emotional breakdown that led to a brief stay in a sanitarium. As with all men who boarded Titanic’s lifeboats, Behr encountered whispers about his gallantry. He testified in the aftermath that he was ordered to row the boat, saying, “At that time we supposed there were plenty of lifeboats for all the passengers.”

The media also scrutinized the romantic relationship between Behr and Newsom, who became engaged six months after the tragedy and wed in March 1913. The press covered the “Titanic couple” like a real-life Jack and Rose who had met and fell in love on the ill-fated liner. Despite the pair’s repeated denials, some newspapers erroneously reported the two were strangers thrown together by fate in the lifeboat, while others claimed Behr proposed to Newsom inside the lifeboat.

Williams was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1957, while Behr was enshrined posthumously in 1969. Arguable, however, their greatest triumph was surviving history’s most famous shipwreck.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

From The Daily Telegraph

The secret bond of two American tennis aces who survived Titanic disaster

It is, according to the publisher Randy Walker, the 'greatest story in the history of tennis’.

So as the centenary of the Titanic sinking approaches this Sunday, how salutary that we should be reacquainted with two athletes bound together by their Ivy League education, patrician East Coast stock, eligible bachelordom, and the fact that they survived the most famous maritime disaster in history. Chronicling the story of Richard Norris Williams and Karl Behr remains fraught with sensitivity, even 100 years on. Lydia Griffin, Williams’ granddaughter, has denounced Lindsay Gibbs’ forthcoming novel on their lives as a 'fictional tale spun on a bare scaffold of real events’. Such controversy is regrettable, for theirs is a narrative almost impossible to sensationalise.

The faithfully-rendered 3D version of James Cameron’s Titanic would appear to have nothing on the undercurrents of class, love and valour that their ordeal encapsulated. Williams and Behr were hardly the most celebrated members of Titanic’s manifest when she left Southampton on April 12, 1912. Not when the passengers for her maiden voyage included such titans of American industry as John Jacob Astor IV, Benjamin Guggenheim and George Widener. It turned out that Widener, a streetcar magnate, was not the only representative of Philadelphia high society on board.

For also in his company in first class was one Charles Duane Williams, distant descendant of Benjamin Franklin and father to Richard, known as Dick, a highly promising junior tennis talent. The family had relocated to Geneva once Charles became ill, and the teenage Dick has been said to prefigure Roger Federer by virtue of his domination of the Swiss circuit and the effortless elegance of his play. He and his father had booked on Titanic so that he could compete in the American summer tournaments before enrolling at Harvard in the autumn. In the event, they made the crossing with just minutes to spare, when they disembarked at the wrong railway connection in Paris.

It was on the train that Williams had been shocked to catch sight of Behr, a successful lawyer and confidant of Teddy Roosevelt, not to mention a member of the US Davis Cup team. So accomplished was Behr on a tennis court that he reached the Wimbledon doubles final in 1907, although he found himself in Europe on a strictly non-sporting project. For what guided him was a girl: specifically, 19-year-old Helen Newsom, a friend of his younger sister, with whom he had slipped away to enjoy the sights of Madeira and Morocco on his first transatlantic cruise. The two of them had arranged to meet again when they were next in New York, but Behr decided to surprise Helen on the return journey. Thus did he settle comfortably into Titanic cabin C-148, armed with a diamond ring.

For the first days of the crossing, Behr was preoccupied with winning over Helen’s mother and stepfather, Sallie and Richard Beckwith, both concerned at how he was eight years her senior. Williams instead invested his time on Titanic’s squash courts, a blissful escape brutally truncated when, at 11.40pm on April 14, an iceberg ripped a gash in the hull. At first he was placated — despite the ghastly sound beneath — by the words of his father, who sought to reassure him that if the ship had been punctured, she could float for up to 15 hours: more than sufficient time for a rescue mission. Behr, it is reported, swiftly intuited the severity of the situation, ordering Helen to change into warm clothes and to leave all possessions behind except her jewels. He secured a place in one of the lifeboats only when J Bruce Ismay, managing director of White Star Lines, allegedly told him that men were needed to help the women and children with the rowing.

For Williams, the escape was more desperate. He and his father had tried to retain warmth by riding stationary bikes in the exercise room, but decided to abandon ship once they saw the letters of the ship’s name on the bow slip below the water line. As they spoke on deck, one of Titanic’s huge smokestacks crashed down, killing Charles instantly.

In that second, Dick dived into the freezing Atlantic. “I was not under water very long,” he wrote to a fellow survivor, having saved his life by clinging to a collapsible raft. He would watch as Titanic’s stern flopped into the icy depths at 2.45am, finally encountering Behr aboard Carpathia on the harrowing onward passage to New York. Three months later they would meet once more. This time it was in a fourth-round match of the Longwood Bowl in Boston, with Behr prevailing in five sets. Neither, most extraordinarily of all, would utter a word about the ties that bound them.

Page refreshed : 12th June 2017