Education and Schooling in the New World

As we start to get to know Honorine more as a person rather than an unwanted 'brat' always searching for a father - anyone would do as she didn't have too great a list of attributes, we find that there is a very deep and lasting relationship between her and her mother, Angélique. This deep tie makes Angélique vulnerable to, of all people, Ambroisine who makes a dramatic return in the books as yet untranslated into English. Ambroisine has seen the deep attachment and love mother and daughter have for each other and resents this in a malevolent way as only Ambroisine can conjure! As a result she sets to organising an assassination attempt on Honorine. Honorine is partly protected by the school to which she has gone, more than willingly as it was her own choice to gain and education. Angélique suffers the terrible pangs of being separated from her which she had not experienced with her older children, Florimond, Cantor and the tragically murdered Charles-Henri.

Marguerite Bourgeoys, in addition to founding a congregation also nurtured the 'King's Daughters' (Les Filles du Roi) and established schools.

"In 1652, Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve, the first Governor of Ville Marie (Mary's City) in the small colony known as New France, sailed home to report on the colony's progress over the 10 years since he had established it. He had arrived on the shore of the Saint Lawrence River with some 60 persons, including Jeanne Mance, whose mission was to open a hospital. There was now a fort along the waterfront; some primitive houses had been built; and Jeanne had opened her hospital, the Hotel Dieu.

The settlers were battling hunger, disease, rugged Canadian winters and the constant threat of attacks by the native Iroquois. More help was needed! As he rounded up volunteer settlers, de Maisonneuve knew that eventually, someone would be needed to open a school. Little did Marguerite dream that she was destined be that person! De Maisonneuve went to visit his sister, a member of the Congregation de Notre Dame, a teaching community in Troyes, and discussed the New World situation with her. After careful consideration, she suggested Marguerite Bourgeoys, a devout Catholic from a good family who was strong, healthy and a person of courage and perseverance. Already dedicated to the service of others, she was intelligent, knowledgeable and certainly qualified to oversee the education of Ville Marie's future children.

De Maisonneuve's request was an unexpected challenge to Marguerite. Was God calling her to leave all that was familiar and sail into the unknown? Her family was aghast at the thought! The Carmelites offered to admit her to any convent she chose. After much thought, prayer and reflection, she was convinced that Our Lady was saying to her, "Go. I will not forsake you."

Carrying a small bundle of all that she had kept of her worldly belongings under her arm, Marguerite boarded the St. Nicholas, a crude, comfortless vessel, for the eight-week voyage to Ville Marie. During that time, Marguerite would nurse men struck down by the plague, tend the dying, shroud the dead, and pray with and for the colonists. One hundred survivors arrived in the small, desolate city of Ville Marie on November 16, 1653, where they received a warm and joyous welcome and settled in to a new life.

There were, as yet, no children to teach. Marguerite became housekeeper to the Governor and helped Jeanne Mance to tend the sick. She attended to myriad mundane tasks each day. But prayer was central to her daily life and her spirituality was soon reflected in the hearts of the colonists, for she lived her message. It has been written that, "The works of mercy were her food; compassion was her song."

Marguerite asked to be taken to see the cross that had been erected on Mount Royal in 1643 in thanksgiving for receding flood waters that had threatened to destroy the settlement. She discovered that it had been demolished by the Iroquois, but undaunted, she had a new cross placed on the original site. A cross still stands on that very spot! Another of Marguerite's special projects was the construction of Notre Dame de Bonsecours Chapel, which was begun in 1657 and finally completed in 1678 after many delays. The chapel still stands on the waterfront in Old Montreal and welcomes thousands of pilgrims each year.

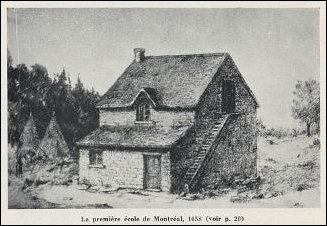

La Première école de Montréal, 1658 dans Roland-Joseph Auger, La Grande recrue de 1653, 1955

Ville Marie's first school opened in an abandoned stable in 1658. Marguerite loved it because it reminded her of the long ago stable in Bethlehem that was Jesus' birthplace. It was here that both native and settlers' children were taught to read, write and work with numbers, as well as prepared for the sacraments. Little girls were taught the basics of homemaking.

Ville Marie's first school opened in an abandoned stable in 1658. Marguerite loved it because it reminded her of the long ago stable in Bethlehem that was Jesus' birthplace. It was here that both native and settlers' children were taught to read, write and work with numbers, as well as prepared for the sacraments. Little girls were taught the basics of homemaking.

In 1659 and 1670, she travelled back to France to find young women to help her. She and her companions adopted the style of dress of their French counterparts, lived on "bread and pottage," and worked for what they needed. When food ran out, someone inevitably appeared at their door with bread and the makings of a meal. The Sisters, as they called themselves, embraced Marguerite's simple spirituality: Love God, love your neighbour, look to Mary as the perfect model of your love.

As the colony grew, so did their teaching mission. They acquired a farm in Point St. Charles, and the land was worked to provide food for the Sisters and their pupils. There, they opened an industrial school which they named La Providence and taught girls trades, farming and household arts. This building, La Maison Saint Gabriel is now a museum which is fascinating to visit. Part of the building dates back to 1668.

The Sisters were actively involved in the Sulpicians' "Mountain Mission," where they taught little girls from Iroquois families. As needs arose, they opened other little schools.

Marguerite became known as the Mother of the Colony through her involvement with the colonists and the "Filles du Roi" (the King's Wards) - young women who were sent to Ville Marie to become wives of the settlers. It was she who welcomed them, sheltered them and prepared them for marriage. She attended many weddings and was often asked to be godmother to their children. Many a newborn child was named "Marguerite."

In 1670, King Louis XIV granted civil status to the Congregation de Notre Dame and in 1675, it was recognized as a secular teaching community of the Church. In 1698, their proposed Rule received the Church's stamp of approval and on June 25 of that year, Marguerite and 23 Sisters of Ville Marie pronounced vows binding then to poverty, chastity, obedience and the education of young girls.

Mother Marguerite remained Superior of the Congregation until 1693, when she was replaced by Sister Marie Barbier, the first Montrealer to join the congregation. For the next four years, she nursed the last of her original companions. At age 77, she began writing her Memoirs. She died on January 12, 1700." (Extract from the Eucharistic Community of St. Luke)

This page looks at the education and schooling as it would have been at the time of the storylines from 'Countess Angélique' to 'La Victoire d'Angélique.'

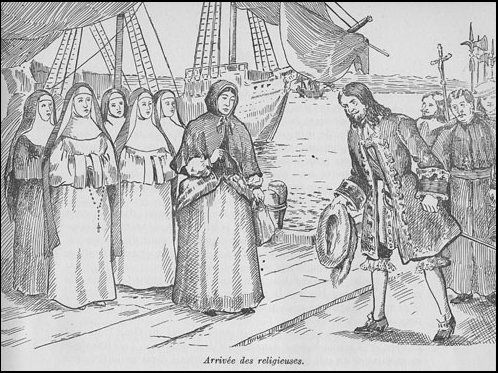

As this charming image by Adélard Desrosiers, from the Petite histoire du Canada, 1933 shows, the nuns who would be responsible for setting up the schools in New France would arrive on ship from their convents in Old France. This image portrays the actual arrival of Marguerite Bourgeoys to the New World.

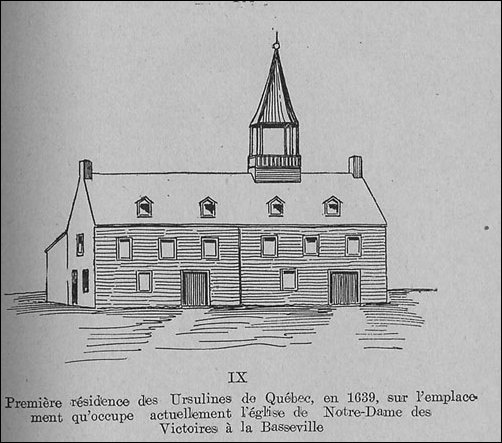

More than likely the accommodation for these brave pioneer women would have been a purpose built convent as seen here in an image by dans Joseph Trudelle, from Les Jubilés, églises et chapelles de la ville et de la banlieue de Québec 1608-1901, 1901.

This specific example is recorded as the 'First Ursuline residence in Quebec, 1639' on which now stands the Church of Notre-Dame des Victoires à la Basseville.

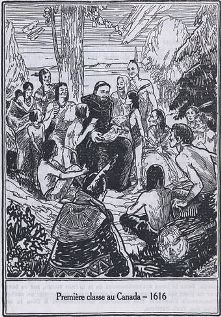

Prior to the arrival of the teaching nuns, most of the education would have been initiated by the Jesuits who would also have been concentrating on their principal mandate of converting the native American Indian tribes. It is likely that this education did take place in the open as portrayed here in another charming illustration this time by an unknown artist but placed at around 1616 from Fastes trifluviens : tableaux d'histoire trifluvienne sous le régime français, 1931.

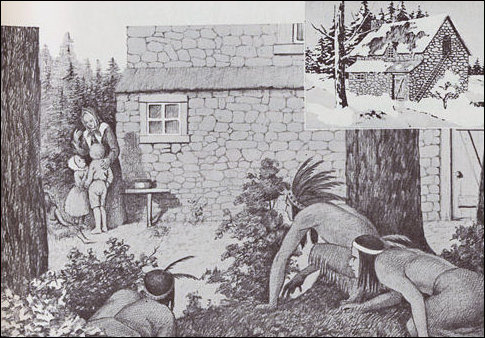

It must have been a real source of interest to the Native American Indians, know for their curiosity to see that white women were now involved with the education process. It is very likely that they would have crept up to the teaching establishments to see what was happening in the curious new world that was being imposed on them.

Here is an undated image of Marguerite Bourgeoys being surveyed by the Native American Indians from La Bienheureuse Marguerite Bourgeoys, sa béatification, 1951.

Here is an undated image of Marguerite Bourgeoys being surveyed by the Native American Indians from La Bienheureuse Marguerite Bourgeoys, sa béatification, 1951.

How would all this have looked to Honorine?

Perhaps like this:

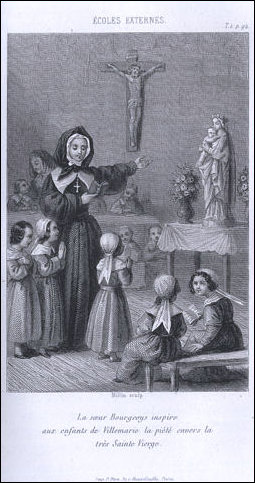

La soeur Bourgeoys inspire aux enfants de Villemarie la piété envers la très Sainte Vierge

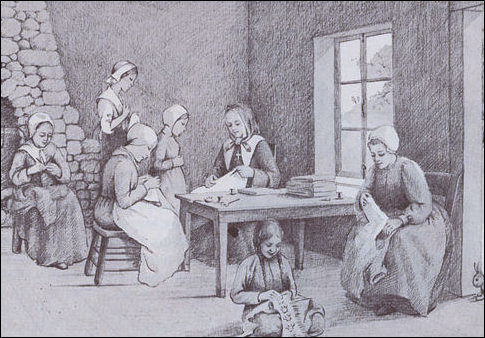

Honorine informs her parents that she wishes to be schooled and is sent to the local convent school in Québec and her lessons may have taken a form not unlike this image where the European maids would have been taught to embroider and sew and the native girls encouraged to hone their skills in the weaving of Wampum. Another very realistic illustration from La Bienheureuse Marguerite Bourgeoys, sa béatification, 1951.

However the local school was not enough for Honorine who then announced she wanted to be educated by the Ursulines, as had her mother before her in Poitou - this would prove heart-rending for both of them, but for Angélique the greater sacrifice. She held on to the thought that her beloved daughter, who would now be apart from her physically in Ville Marie, would be taught and nurtured by Marguerite Bourgeoys.

Pensionnat de la Congrégation à Villemarie - from Étienne-Michel Faillon, Mémoires particuliers pour servir à l'histoire de l'Église de l'Amérique du nord, 1853 - although undated, this illustration does portray the time of Marguerite Bourgeoys and therefore the Angélique and Honorine time and date lines.

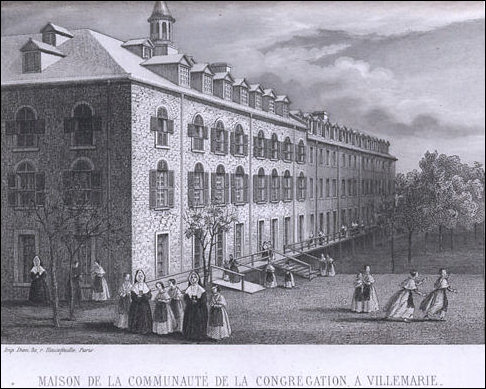

Maison de la communauté de la Congrégation à Villemarie

Again from Étienne-Michel Faillon, Mémoires particuliers pour servir à l'histoire de l'Église de l'Amérique du nord, 1853 an illustration showing the actual nunnery.

With thanks to podcastmcq.org for the images contained in this page

Return to Top / Angélique Home Page / Home Page

Page refreshed : 11th January 2017