Angélique and the King

Angélique and the King

- so what is this book all about? Angélique's triumphant return to the Court of Louis XIV at Versailles, with a brand new husband in tow.

Angélique and the King

- so what is this book all about? Angélique's triumphant return to the Court of Louis XIV at Versailles, with a brand new husband in tow.

What do we know about this husband, this Philippe du Plessis-Bellière? He's her cousin and she had to blackmail him into marrying her. This, following on from their childhood when he had dubbed her the 'Baroness of the Doleful Dress.' Perhaps it was fitting that she should now outshine her peacock of a husband!

Oh what a job-lot Angélique got herself here - two 'boys' (her sovereign and her king) cut from the same cloth. Constantly subjecting her to their own petty jealousies and infantile behaviour. Added to this mix is the ever present 'Monsieur', the King's brother - or maybe that was part of his trouble, always being known as the 'King's brother', never having an identity of his own, always knowing that he has to be placed second to anything big bro Louis achieves - except when it came to his own louche existence in which he revelled, knowing that he had none of the responsibilities of state to hold him back.

Much emphasis is placed on fashion in this period, not least because Louis himself was a dedicated inventor of his own image - and as I like fashion and the whole concept of this complex and seriously flawed period I make no apologies for indulging myself and, hopefully, you the viewer.

Original steel engraving drawn by F.H. Lalaisse, engraved by Prot 1834

You may have guessed that much as I love these books, I haven't yet found one male character that I consider worthy of our eponymous heroine (and yes, at this stage that still includes her former husband, Joffrey). So, before I say farewell to the non-distaff side - here come the boys:

Showing how the fashion of the day should be worn - posturing to perfection from the new 2016 production of 'Versailles'

Original wood engraving drawn by Cehric - Wittig, engraved by Ed. Schempp. Original hand-coloured. 1870

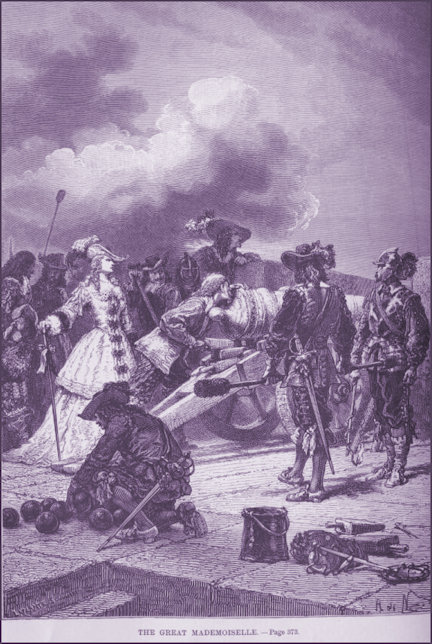

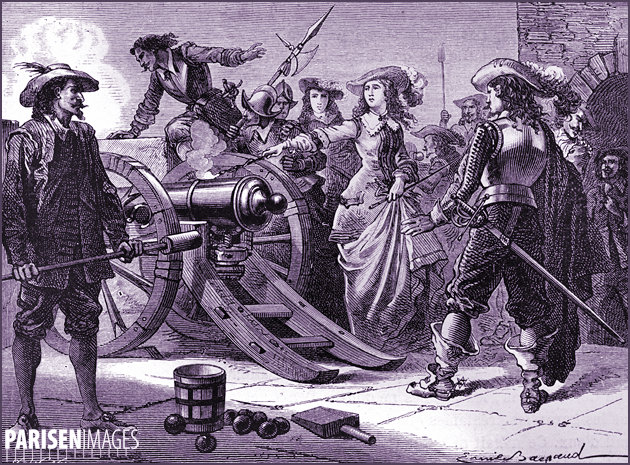

La Grande Mademoiselle at the Court of France : 1627-1693

I found these remarkable images of the Grande Mademoiselle and thought together with Ninon the great wit of her day and Catherine the great sinner (or sinned against) deserved to be included in the book that centres in and around Versailles. Of course we meet la Grande Mademoiselle in Book 1 when Angélique begs for her intervention and receives her protection from the cousin even Louis did not wish to cross!

Anne-Marie-Louise d'Orléans - a cousin to Louis XIV and known in her time and to posterity as "la Grande Mademoiselle" - is still remembered in France today for her unconventional life and heroic deeds. Her "Memoirs", first published in 1718 and initially suppressed in France, remain a major source of information on the period's political and social events as well as a page-turning melodrama of court intrigue. Mademoiselle also left behind a number of other works - literary portraits of the prominent personalities of her day, letters, satirical short stories, and two essays on religion - which, together with her memoirs, stand as an unusual achievement for any 17th-century woman, let alone one so high-born and wealthy. This comprehensive biography of this remarkable woman draws on Mademoiselle's own writings as well as Vincent J. Pitts' own command of her times. Viewed through her writings, the events of Mademoiselle's life offer a perspective on several aspects of 17th-century France - the evolution of the Bourbon monarchy over the course of the century, the dynamics of aristocratic resistance to the centralizing power of the state, and the debate over the role of women in public and private life. As both an active participant in and a keen observer of the great events of her time, la Grande Mademoiselle helped define her age even as she challenged the limitations it placed upon her.

(source: Nielsen Book Data)9780801864667 20160528

La Grande Mademoiselle, 2nd July 1652 at the Bastille - Image courtesy of ParisenImages

The Mystery that is Rakoczy

Recently, in December 2015, following some dialogue with a Hungarian fan of the books, I discovered that the Character of Rakoczy, revolutionary nobleman of Hungary, who appears in the English 'Cast of Characters/Dramatis Personae' of this book has been expunged in the Hungarian version! That isn't all - at least four pages of original French dialogue between Angélique and Rakoczy have also disappeared.

This phenomenon is covered in a separate page devoted to this anomaly.

Poisoners, Alchemists, Potion-Makers v Courtesans

Luckily for me I have already written the review for this book elsewhere  and as I keep stressing, this

and as I keep stressing, this  web-site is a tribute to Anne Golon and her great work and to the fact that she stirs up such emotions (in me and multi-thousands of others) and introduces such thought-provoking ideas, characters, historical characters and plots into her continuing saga.

web-site is a tribute to Anne Golon and her great work and to the fact that she stirs up such emotions (in me and multi-thousands of others) and introduces such thought-provoking ideas, characters, historical characters and plots into her continuing saga.

So the purpose is not to dissect the stories or do a critique but to embellish what is already there by running some comparable commentary. In this book the two outstanding areas for me, just happen to concern strong women - Ninon de Lenclos (right) the great and respected courtesan and the equally famous and infamous poisoner La Voisin (left).

Women dominated much of French cultural life in the 17th century; something that may not be apparent on a day to day basis unless one is a historical scholar or an avid reader, but it is easy to see how the character of Angélique is able to develop under these auspices throughout the series. It is very astute of the author to have picked up on this to add character and strength to her heroine, to allow her to walk amongst men as their equal. French women in positions of prominence renewed many of the lost traditions of preceding golden ages, setting the style for the centuries to come with their invention of 'the salon', at the head of which sat Ninon.

Both professions have been around since time immemorial whilst ever there has been the need to provide medication and comfort. Traditionally, however, the Alchemists and Potion-makers have been men - either religious (monks) or from the middle and far east where Christianity had not yet made its mark, and indeed so venerated were the followers of Allah and Buddha that they were not afraid of offering their healing services in the Western courts, knowing they would not be subjected to any witch hunts (such as experienced by Joffrey de Peyrac). Assassinations are also usually the province of men - but poison is, we are informed favoured as the preferred assassination tool of women (poor Lucrezia). Courtesans, in the forefront of acceptable behaviour were usually women.

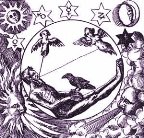

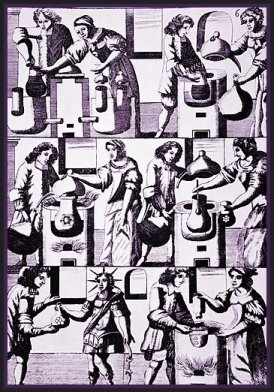

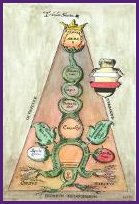

Alchemy preparations. 17th-century artwork titled 'The alchemist and his wife in the hermetic laboratory'. Hermeticism is based on worship of the Hellenistic Egyptian god Hermes Trismegistus. Six different stages are shown here, from preparing the treatments, to heating them over a fire. This is a woodcut from 'Mutus Liber' (Silent Book), a book on alchemy that was published in La Rochelle, France, in 1677. The author was the French apothecary Isaac Baulot.

Alchemy preparations. 17th-century artwork titled 'The alchemist and his wife in the hermetic laboratory'. Hermeticism is based on worship of the Hellenistic Egyptian god Hermes Trismegistus. Six different stages are shown here, from preparing the treatments, to heating them over a fire. This is a woodcut from 'Mutus Liber' (Silent Book), a book on alchemy that was published in La Rochelle, France, in 1677. The author was the French apothecary Isaac Baulot.

Rosicrucian alchemical works - Thanks to Science Photo for the imagery

And so to the two ladies who will feature on this page - fame or infamy is attached to both. Their names, fortunes and misfortunes were made at Versailles at the Court of Louis XIV. Ninon had the 'ear' of Louis - it is said that 'whenever he wanted a second opinion, he was known to ask "What would Ninon do?" because the Sun King, during his long reign, was purported to have mostly ignored the views of his advisors and peers.' Catherine Deshayes Monvoisin ("La Voisin") on the other hand nearly brought down Louis' court with the 'Affair of the Poisons' luridly sub-titled as 'Murder, Infanticide and Satanism at the Court of Louis XIV.' That, most certainly, may have proved an interesting conversation piece to eavesdrop between Louis and Ninon.

Ninon - fact or fiction?

The fable starts with a mysterious character called a 'Noctambule' or 'Sleepwalker' - perhaps 'Dreamweaver' may have been more accurate. He tells her he has come to make her an offer, one that will only hold if she promises eternal silence, and gives her the following three choices: the highest position in the land, great riches and fame or everlasting beauty; she may choose only one of these. He told her he had offered the same three options to four of her predecessors and named them as Semiramis (the Assyrian Queen or Queen of Sheba), Helen of Troy, Cleopatra and Diane de Poitiers. No such choice for Catherine Deshayes Monvoisin then?

Ninon - the reality

Anne de Lenclos, better known as Ninon, was born in 1620 to a middle class family in the fashionable Marais district in Paris. Her death in 1705, aged 85, assured her status as a national treasure.

As a young woman without a dowry, history records that choices for women in this predicament usually meant they could marry, join the Church, become a governess, or follow the road to prostitution. Fate decreed that she travelled down the fourth branch of the listed choices. Who knows what motivated this decision? Was it that she tragically, conceived and gave birth to a son who subsequently committed suicide because of unrequited love, her love? Or was that another of the many myths associated with Ninon the legend?

Significantly Madame de Maintenon, on marrying Louis, turned her hand to clearing up the question of the Huguenots (was the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes her idea?) and cleaning up prostitution which was rife in France during this decadent period.

Ninon, the courtesan, was in a slightly better place inasmuch as she would wear fine clothes and kept a respectable (on the surface of it) house, giving her the opportunity of entertaining and in some instances keeping married men. Unfortunately for Ninon's enterprise, neighbouring working class and middle class families began complaining to the authorities about her and the authorities were obliged to hire many more policemen to cope with the fallout. It is recorded that on more than one occasion, Ninon had to flee to a powerful protector when complaints escalated. Maintenon urged Ninon to change her inimitable ways by inviting her to live with her at Versailles. But Ninon, who had power over men’s sexual imaginations as much as their bodies, did not practise the importance of the moral code of living up to personal responsibilities or family values. More interested in men than women Ninon did not heed Madame de Maintenons well-meant but misguided good intentions.

"Persons of Quality dress 1664 and a Court Lady from 1668 from a contemporary engraving."

"Ninon’s salon at 28 rue des Tournelles in the Marais soon became the place to be for aspiring men about town and it was never boring. According to the memorist, the Duke de Saint-Simon, the word that summed up Ninon and her salon was “integrity” -- no cards or loud laughter, no arguments or discussions about religion or politics. Ninon set the tone with her lightness of touch and her appreciation for all forms of art and culture, always spiced with wit and music (she played the lute very well). She was not a snob either. Although her salon was initially all male, in later life it attracted women from both the aristocracy and the middle class who wanted to learn how to live their lives as successfully -- intellectually and sensually -- as she had done and mothers introduced their children there before they were turned loose in society. Ninon was influenced by Montaigne’s ideas of political moderation and she knew and practiced Epicureanism, the honourable pursuit of pleasure. At her own salon she was protected by her “birds” -- intellectuals like la Fontaine and la Rochefoucauld, some of whom got to sleep with her. She tended to be faithful in short bursts. All this made her a perfect target for local preachers who railed against decadence and immorality, yet she was a target more for her free-thinking and intellectualism than for her libertinism.

Ninon in her heyday became the leading critic of the arts and literature. Molière observed of her: “She has the keenest sense of the absurd of anyone I know.” Some would say there is nothing inherently superior about someone who writes their ideas down for posterity (like Molière) over someone for whom letter-writing and stimulating conversation are equally important (like Ninon). We can get a glimpse of Ninon’s intellectualism in her letters, for example the fine series to the Marquis de Sévigné, the son of Madame de Sévigné, on the subject of how to capture a lover. The inevitable happened of course: the Marquis fell in love with Ninon instead.

However, we don’t want to praise Ninon too highly since she was still sleeping with practically anyone she pleased, including monks and priests, well into her eighties! Indeed, if we are looking for role models, Madame de Sévigné herself offers a preferable alternative to the path taken by Ninon. Isn’t it better for a woman to marry, in the hope that her husband will die young, leaving her all the money, as happened to Madame de Sévigné? By not marrying, Ninon achieved little more than any dilettante. She deluded herself if she thought she could ever change society on the basis of charm and wit alone. She also failed for posterity’s sake, for what great works of art remain as a testament to her genius? What aristocratic title and property did she ever attain? None. What was the nature of her fame? As a courtesan? She barely rates in the history books."

(Thanks to Sexual Fables for the quotation above.)

Voltaire, one of her greatest admirers wrote much about Ninon de Lenclos, superstar, but even he was driven, probably out of pique at her growing popularity, to state “If this mania continues, we shall soon have as many Histories of Ninon as of Louis XIV.” I don't suppose it helped that she wrote her own book as well!. Molière observed of her: “She has the keenest sense of the absurd of anyone I know.” That, actually makes a lot of sense!

"Who was this Ninon that an absolute monarch like Louis XIV would seek her advice? She was a French author, courtesan and patron of the arts, whose long life lasted almost as long as the The Sun King's reign in France. In her lifetime, she was known as the sine qua non of courtesans, her salons were attended by some of the greatest minds in France, including Racine, Corneille, de François, duc de la Rochefoucauld and Molière, who tried out all his plays on her first.

After her death, Saint-Simon summed up her career as: "A shining example of the triumph of vice, when directed with intelligence and redeemed by a little virtue." Her prowess with men was so well known that there is a urban legend that for years after her death, the women of Versailles sued to petition her be-ribboned skull for erotic success.

Ninon lived to be 85. Although she no longer went by her nickname, preferring Mademoiselle L'Enclos, she still had lovers up until the very end. In her later years, she became enamoured of her lawyer, François Arouet's son, also named François who later went by the name Voltaire. In her will she left 2,000 livres for him to buy books. Ninon regretted nothing in her life except aging. "Old age is a woman's hell," she said. On her deathbed, she composed this final verse:

I put your consolations by,

And care not for the hopes you give:

Since I'm old enough to die,

Why should I longer wish to live?

After her death, she was eulogized as a sex icon, the subject of numerous plays, books, and myths."

(Thanks to Scandalous Women for the quotations above - the full article can be found here.)

Catherine Deshayes Monvoisin ("La Voisin")

If Anne, born into a middle class family had but four choices to shape her future what of someone like Catherine who graduated from abortionist to poisoner? Should one have sympathy for her?

Her life is less well-documented than that of the divine Ninon, which presupposes that her earlier life was not as homely or glamorous. Everything recorded about her points to her practicing witchcraft so we can be fairly safe in assuming that she was unwanted, probably a slum child. Needless to say the usual norms and prejudices associated with witchcraft would also apply to this antithesis of the middle classes.

However, one way or another Catherine entered Versailles society because she could offer the glittering ladies and gentlemen of the court services that could not be procured (openly) elsewhere. Having started practicing medicine, at which she may have been very talented, and which certainly paid the bills run up by her not too successful jeweller husband (perhaps that is where she began coveting the lifestyle that real jewels could provide) she obviously found she needed to expand her repertoire by placing abortions on the menu. Certainly the relief of ridding oneself of an unwanted, unplanned or embarrassing conception must have appealed to many of the court ladies and courtesans who would have paid large sums for the privilege. I suspect they continued paying for a long time afterwards as this sort of secret would encourage blackmail from many quarters.

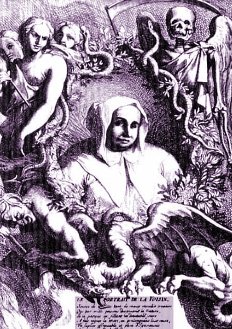

A contemporary engraving of La "Voisin" showing her surrounded by macabre images and 'familiars'.

Shunned by society, but used by them, why should Catherine not have made the most of her opportunities?

But like many others she became greedy and found herself as a leading player in the "Affaire des Poisons" which brought such devastation to the reign of Louis XIV - it was her testimony which brought about the downfall of many well-placed members of the aristocracy and known favourites of the King.

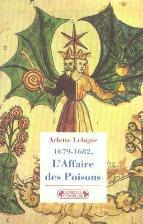

Anne Somerset had researched this turbulent period and written the book entitled 'The Affair of the Poisons' - the two quotes below sum up the book and then the second part fills out a few more details:

"The 'Affair of the Poisons' was a scandal at which 'all France trembled' and which 'horrified the whole of Europe' as it implicated a number of prominent persons at the court of King Louis XIV in the late 17th century. Parisian society was seized by a fad for spiritualist seances, fortune- telling, and the use of love potions. The most celebrated case was that of La Voisin, a midwife and fortune-teller whose real name was Catherine Deshayes Monvoisin and whose clientele included the Marquise de Montespan, Olympe Mancini and Marshal Luxembourg. No formal charges were made, and there is no evidence that they were seriously implicated, yet a permanent stain was left on their names. La Voisin was burned as a poisoner and a sorceress in 1680. A special court was instituted to judge cases of poisoning and witchcraft, and the poison epidemic came to an end in France. This bizarre witch-hunt, which embroiled the gilded denizens of Versailles with the most sordid dregs of Paris society, remains both a fascinating enigma and an utterly compelling story."

"The Affair of the Poisons, as it became known, was an extraordinary episode that took place in France during the reign of Louis XIV. When poisoning and black magic became widespread arrests followed. Suspects included those amongst the highest ranks of society. Suspects were tortured and numerous executions resulted. Anne Somerset, whose last book, Unnatural Murder was also a story of true crime, albeit some sixty years earlier, shows that the Affair of the Poisons actually began with a murder when the Marquise de Brinvilliers was executed after being convicted of poisoning three members of her family. In the French court of the period, where sexual affairs were numerous, ladies were not shy of seeking help from the murkier elements of the Parisian underworld and fortune-tellers supplemented their dubious trade by selling poison. It was not long before the authorities were led to believe that Louis XIV himself was at risk. With the chief of Paris police alerted, every hint of danger was investigated. Rumours abounded and it was not long before the King ordered the setting up of a special commission to investigate the poisons and bring offenders to justice. No one, the King decreed, no matter how grand, would be spared having to account for their conduct. The royal court was soon thrown into disarray. The Mistress of the Robes and a distinguished general were among the early suspects. But they paled into  insignificance when the King's mistress was incriminated. If, as was said, she had engaged in vile Satanic rituals and had sought to poison a rival for the King's affections, what was Louis XIV to do? Anne Somerset has gone back to original sources, letters and earlier accounts of the affair. By the end of her account she reaches firm conclusions on various crucial matters. The Affair of the Poisons is an enthralling account of a sometimes bizarre period in French history."

insignificance when the King's mistress was incriminated. If, as was said, she had engaged in vile Satanic rituals and had sought to poison a rival for the King's affections, what was Louis XIV to do? Anne Somerset has gone back to original sources, letters and earlier accounts of the affair. By the end of her account she reaches firm conclusions on various crucial matters. The Affair of the Poisons is an enthralling account of a sometimes bizarre period in French history."

Catherine Deshayes Monvoisin (La Voisin) (1640-1680) accused sorcerer and convicted poisoner in France ended her life by being burned at the stake on February 22, 1860. A fate, in the face of it, that she shared with another major player in the Angélique saga - Joffrey de Peyrac.

Did Catherine deserve her fate? Certainly she seemed to have been involved with every sort of degrading practise - she joined up with Etienne Guibourg, a de-frocked priest who performed the Black Mass parodying the Christian version and requiring human (baby) sacrifices, not to mention cats, cockerels and any other unsuspecting animals their blood lust craved. She teamed up with magician 'Abbott Le Sage' (Adam Coeuret) - also burned at the stake in the Place de Grève in 1682 - and created love potions containing such choice ingredients as bones from toads, teeth from moles, Spanish flies, iron filings, human blood and the dust of human remains.

Her customers at court are purported to have included Olympe Mancini, the Comtesse de Soissons (who sought to dispatch Louise de La Vallière), her sister Marie Anne Mancini, the Duchesse de Bouillon, François Henri de Montmorency-Bouteville, the Duc de Luxembourg, Françoise-Athénaïs, the Marquise de Montespan and the Comtesse de Gramont ("La Belle Hamilton"). She was therefore mixing with the best in the land and as good as they were or, on the other side of the coin, they were as low as she was and probably not as rich. Catherine would have accumulated a vast amount of money by now - but not the 'entry' into society.

Her customers at court are purported to have included Olympe Mancini, the Comtesse de Soissons (who sought to dispatch Louise de La Vallière), her sister Marie Anne Mancini, the Duchesse de Bouillon, François Henri de Montmorency-Bouteville, the Duc de Luxembourg, Françoise-Athénaïs, the Marquise de Montespan and the Comtesse de Gramont ("La Belle Hamilton"). She was therefore mixing with the best in the land and as good as they were or, on the other side of the coin, they were as low as she was and probably not as rich. Catherine would have accumulated a vast amount of money by now - but not the 'entry' into society.

How these ladies must have trembled when Catherine started telling all she knew and naming names in the Affair of the Poisons - two of the King's Favourites past and present in a position to be exposed and named and shamed publicly!

But it was a contemporary of these fine ladies Marie-Madeleine-Marguerite d'Aubray, the Marquise de Brinvilliers who was the real loser and who became as notorious as Catherine herself. Marie-Madeleine-Marguerite tried to implicate Athénaïs but as both history and the Angélique saga tells us, Athénaïs survived the scandal although it tarnished her reputation badly. Marie-Madeleine-Marguerite d'Aubray also became far better known to us as the Marquise de Brinvilliers also suffering the fate of burning at the stake in the Place de Grève, but only after decapitation (and a bit of water torture). She was also the instrument of cleansing the Royal Court of many alchemists, fortune-tellers, herbalists and charlatans most of whom were probably practicing harmless remedies but who were nevertheless brought to trial wholesale. The fate of many of these will not have been recorded or will have been lost in the lists of time.

Is Catherine - Saint or Sinner - you decide!

A précis of the Affair of the Poisons as found on Amazon.co.uk

The Affair of the Poisons, as it was known, was a scandal at which 'all France trembled' and which 'horrified the whole of Europe' as it implicated a number of prominent persons at the court of the Sun King, King Louis XIV in the late 17th century. It began with the trial of Marie Madeleine d'Aubray,Marquise de Brinvilliers, who conspired with her lover, Godin de Sainte-Croix, an army captain, to poison her father and two brothers in order to secure the family fortune and to end interference in her adulterous relationship. The marquise fled abroad, but in 1676 was arrested at Liege. The affair greatly worked on the popular imagination, and there were rumours that she had tried out her poisons on hospital patients. She was beheaded and then burned. The Brinvilliers trial attracted attention to other mysterious deaths. Parisian society had been seized by a fad for spiritualist seances, fortune-telling, and the use of love potions. The most celebrated case was that of La Voisin, a midwife and fortune-teller whose real name was Catherine Deshayes Monvoisin and whose clientele included the marquise de Montespan, Olympe Mancini (niece of Cardinal Mazarin and mother of Prince Eugene of Savoy), and Marshal Luxembourg. No formal charges were made, and there is no evidence that they were seriously implicated, yet a permanent stain was left on their names. La Voisin was burned as a poisoner and a sorceress in 1680. A special court, the chambre ardente [burning court], was instituted to judge cases of poisoning and witchcraft, and the poison epidemic came to an end in France. The affair was symptomatic of the witchcraft trials of the period throughout Europe. This bizarre witch hunt, which embroiled the gilded denizens of Versailles with the most sordid dregs of Paris society, remains both a fascinating enigma and an utterly compelling story.

Hotel Beautrellis

As she went about restoring Joffrey's properties (by fair means or foul - she was a mean card 'shark' when it suited her to be), foremost in her mind had been the happy home in which she had been received in Paris. It was where she spent her last nights with her husband before his mysterious disappearance and the place where Cantor was conceived in love. It also became the scene which provided her with the clues to venture to North Africa (Candia) in pursuit of her lost love. Of particular significance is that Savary chose to hide out at the Hotel Beautrellis awaiting the return of the Peyrac family. Florimond also knew the house and grounds well and it was he who showed his mother the secret passage leading away from the property after the King had put her under 'house arrest'.

Whether or not the Hotel Beautrellis existed is a matter for speculation but the road sign confirms the existence of the road for its setting.

Magical Properties - the mysterious Moumie

A mysterious substance coveted by Savary in a number of books - the closest I can find is a substance more commonly known as 'Shilajit' more about which can be found on the internet.

Image courtesy of Shilajit Power

Mohamed Bakhtiary Bey

Antoine Coypels' depiction of Louis XIV greeting Mohamed Bakhtiary Bey, ambassador of Sultan Hossein Shah of Persia (Safavid Dynasty) at the Galerie des Glaces of Versailles on 19th February 1715.

A fictionalised account of this historical meeting was depicted in a French Film entitled "Angélique et le Roi" (1966) starring Sami Frey in the role of the Persian Ambassador seduced by a French Courtesan Angelique portrayed by Michelle Mercier. Also featuring in this film is Robert Hossein (son of famous music composer of Iranian decent Andre Aminollah Hossein) in the role of Joffrey de Peyrac the enigmatic husband and love interest of the beautiful Angélique. Jacques Toja plays King Louis XIV of France.

From the Palace of Versailles web-site:

"19 February 1715

After Genoa and Siam, the embassy of Persia was the third and last to be received by Louis XIV in the Hall of Mirrors. The king used the occasion to give an ultimate demonstration of his royal pomp and glory. But this was a strange diplomatic mission…

On 19 February 1715 at 11 am, Mohammed Reza Beg, ambassador extraordinary, made his entry into the Château on horseback with his retinue, accompanied by the presenter of ambassadors and the lieutenant of the king’s armies. Crowds filled the avenue de Paris and the courtyards to attend the arrival of this exotic envoy. The courtiers crowded into the Hall of Mirrors, where four tiers of seats had been set up for them. Only the most sumptuously dressed could enter. The Hall of Mirrors was packed, with many foreigners present. At the back, the king on his throne was surrounded by the future Louis XV and his governess, Mme de Ventadour, the Duc d’Orléans and princes of the royal blood. The painter Coypel and Boze, Secretary of the Academy of Inscriptions, stood below the platform to record the event.

Concerned to make an impact, Louis XIV was dressed in a black and gold outfit covered with diamonds, worth a total of 12.5 million livres. An astronomic amount! The king had to change out of it after dinner because it weighed so much. His entourage was equally resplendent: the Dauphin was also covered with jewels. The Duc d’Orléans wore embroidered blue velvet studded with pearls and diamonds. As for the legitimate sons of the king, the Duc du Maine and the Comte de Toulouse, one wore a set of diamonds and pearls and the other a set of precious stones!

The ambassador entered the Hall of Mirrors, accompanied by an interpreter. Pretending to understand French, he said he was unhappy with the translation. After a long audience, he attended the dinner given in his honour. He left Versailles after visiting the young Louis XV whom he liked.

The purpose of this mission was uncertain. When he came to Paris on 7 February, according to Saint-Simon, Mohammed Reza Beg had no accreditation. The king, convinced of his ambassadorial status, received him. He lodged him in the city with his chief valet Bontemps. But his suite was unimpressive, as were his presents to the king. He was said to be only a provincial dignitary putting on a show for his own ends! The king received him for the last time on 13 August. It was his last diplomatic act. The embassy inspired the Lettres Persanes of Montesquieu, published in 1721."

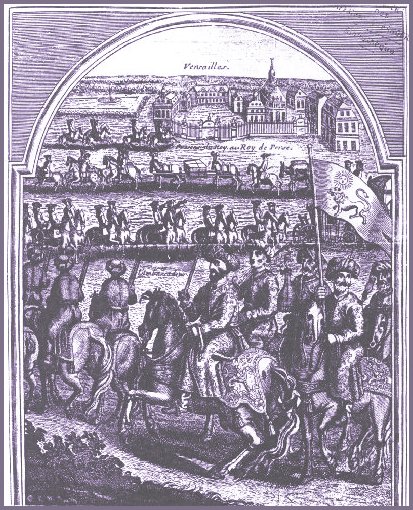

A detail identifying the palace at Versailles

Lithograph detailing the Arrival of the Persian Ambassador to the court of Louis XVI at Versailles

A detail of the lithograph clearly identifying Versailles as the destination

Page refreshed : 29th August 2019 (G)

Helen of Troy (as portrayed by Elizabeth Taylor)

Helen of Troy (as portrayed by Elizabeth Taylor)